Departure for the Promised Land? Unmet Expectations of Immigrants and Their Consequences

The future looked bright when Jennifer moved to Switzerland for her new job over a year ago. And yet, here she was, sitting at the kitchen table, frustrated by the events of the past week, not getting the promotion she was promised, and no one turning up for her birthday party. Like Jennifer, thousands of highly qualified immigrants come to Switzerland every year, and with their high levels of education and salaries, they receive little attention when it comes to integration: we tend to assume that everything is fine.

It is easy to forget that moving to another country is always coupled with risks, whether you are a refugee or a highly qualified immigrant like Jennifer. Migrants take on a lot when they leave their home countries, and they have no way of knowing whether it will pay off in the end. The success of their migration project is only partly in their hands. Things like legal regulations that make it difficult to enter the local labor market, language barriers, and prejudice can thwart their plans. Thus, migration pretty much resembles a step into the unknown—a risk that migrants like Jennifer and others seem to be willing to take to improve their lives, and those of their families.

This element of risk in migration has led some scholars to think of migration as a game in which migrants gamble with their future. Migrants think they can calculate the risks they take, when in fact they are exposed to the game of migration. Jennifer certainly did not expect her employer to renege on the promise of a promotion, and she never imagined that finding good friends in Switzerland would turn out to be such a struggle, having always considered herself a very sociable person.

High Hopes, High Disappointment

Research suggests that highly qualified migrants embody the (overly) confident gambler when compared to their less qualified counterparts. The highly qualified are thought to have particularly high expectations of migration as an opportunity, and of fitting in and being treated equally and fairly.

Take Jennifer, for example, she was brought up in a secular household by highly educated parents with prestigious jobs. Because of her privileged background, she never experienced discrimination or the feeling of being left behind. She grew up confident and with the attitude that everyone deserves to be treated equally and fairly, including herself. The fact that she has a degree from a prestigious university has not really diminished her expectations of migration, as she knows that she is quick to grasp things and that she belongs to a desirable group of immigrants who are well received by the locals and the government.

However, her social background and qualifications were of little help when she realized that her expectations did not match reality. Although one could see Jennifer with her well‑paid job and low‑profile life as an example of successful integration, she didn’t feel integrated at all—let alone at home—when she was sitting at her kitchen table. Instead, she felt depressed and thought about leaving the country. It seems that if expectations are high, disappointment may follow.

Should We Worry?

Jennifer’s situation is exemplary for many highly qualified immigrants, and researchers argue that their unmet expectations of migration are particularly consequential. For immigrants, they can cause stress and frustration by triggering existential anxieties and feelings of not being welcomed and respected. Unmet migration expectations can therefore badly affect mental health, leading immigrants to isolate themselves, withdraw from social life or even leave the country.

For the governments, these issues threaten social cohesion through reduced participation in social life, and because immigrants are crucial in helping newcomers to settle. They also increase costs to the health care system and exacerbate labor shortages at a time of declining birth rates and aging populations.

So, should we be worried about Jennifer and her skilled peers? To find out, we explored what consequences unmet migration expectations have for immigrants in Switzerland, and whether they are indeed particularly consequential for highly qualified immigrants. We analyzed data from the Migration Mobility Survey (MMS), a longitudinal study of adult immigrants who arrived in Switzerland from all over the world in 2006 or later. The longitudinal design of the study allows us to track whether people change.

To find out whether immigrants’ migration expectations have been disappointing, the MMS asked participants about their (dis)satisfaction with the decision to move to Switzerland. We assume that migration expectations will be disappointing if the dissatisfaction of the participants increases in the course of the study. To find out about the consequences of unmet migration expectations, we look at immigrants’ attachment to Switzerland. Immigrants’ attachment to their destination country tells us much about immigrants’ bonds to their new home, whether they feel welcome, accepted, and part of the society.

Imagine that we interviewed Jennifer for the first time a few months after she arrived in Switzerland, when everything was still great, and a second time a year later after her mental breakdown. We can now examine whether her increase in dissatisfaction with her move to Switzerland between the first and the second interview actually led to a decrease in her attachment to the country.

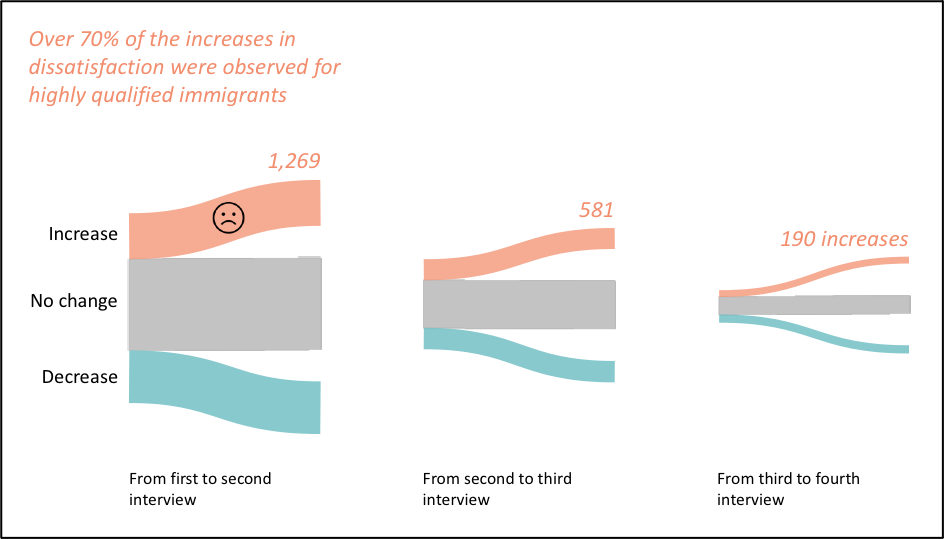

As we can see in Figure 1, Jennifer is not an isolated case: Immigrants increased their dissatisfaction with the decision to move to Switzerland 2,040 times during the MMS (orange upward-flowing streams). 1,448 of these were highly qualified immigrants like Jennifer, representing more than 70 percent of all increases.

Figure 1 Immigrants’ dissatisfaction with the decision to move to Switzerland increased 2,040 times during the survey.

Note. Increases in dissatisfaction are represented by the orange upward-flowing streams. Created with Sankeymatic

Data. MMS, waves 1-4, own calculations.

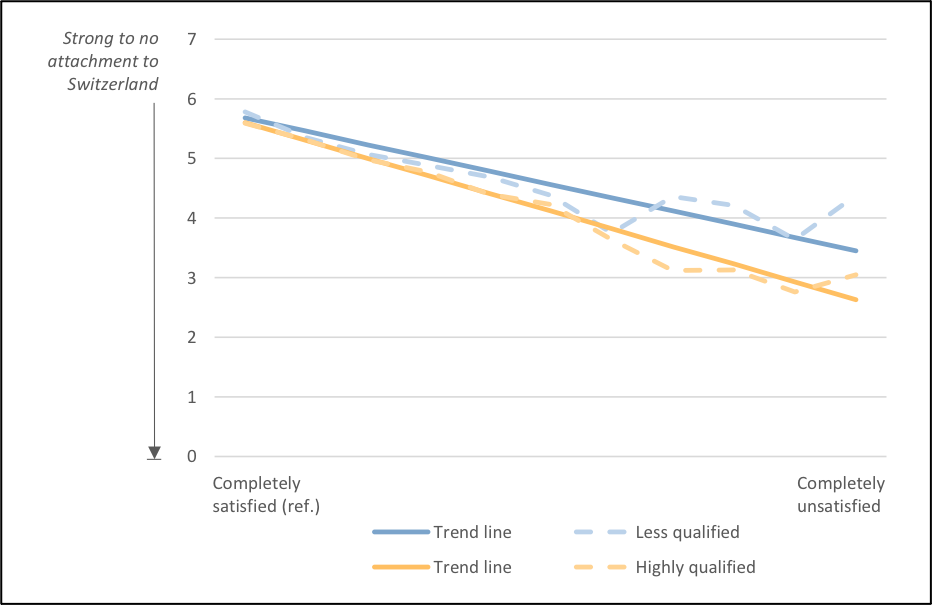

So, what are the consequences of these unmet migration expectations for immigrants? As you can see in Figure 2, we observe a general reduction in the attachment to Switzerland among immigrants who report increased dissatisfaction with moving to Switzerland. We can also see that the reduction in attachment is stronger for highly qualified immigrants than for less qualified immigrants. So, it does seem that highly qualified immigrants like Jennifer have a particularly hard time when their expectations of migration are not met.

Figure 2 Particularly higher qualified immigrants show a decrease in their attachment to Switzerland if their dissatisfaction with the moving decision increases.

Note. Results based on separate fixed effects linear regressions. Data. MMS, waves 1–4, own calculations.

What Now?

What can we learn from the observation that for highly educated immigrants, unmet migration expectations weigh more heavily?

First, both scholars and policymakers need to recognize that integration processes are multifaceted. Simply reducing successful integration to socio-economic success obscures the fact that highly skilled workers are not immune to struggles and difficulties—especially in dimensions that we typically find difficult to quantify. Second, we can respond to this challenge by also quantifying soft factors, such as self-perceived integration, so that we can catch cases like Jennifer’s before they fall through the cracks and avoid additional costs to businesses and society further down the line.

When we think about migration, we have a particular image of immigrants in mind and forget that the reality is often more complex. Integration is not just about how Jennifer is doing compared to—say—Adriano, the Italian waiter in the restaurant next door, but also about how their social lives match their emotional lives.

Andreas Genoni is a postdoctoral researcher at the Federal Institute for Population Research (BiB) in Germany and an associate researcher of the nccr – on the move. His work focuses on international migration and its consequences for individuals, with a particular focus on perceptions of integration and well-being.

Didier Ruedin is a Senior Lecturer at the Swiss Forum for Migration and Population Studies at the University of Neuchâtel and a Project Leader of the nccr – on the move project Narratives of Crisis and Their Influence in Shaping Discourses and Policies of Migration and Mobility.