Behind the EU Pact on Asylum: A Geography of Protection

European asylum policy still has a long way to go to better address protection challenges. The EU’s new Pact on Asylum has been created to manage some of the existing imbalances by assisting countries receiving more seekers with relocations, financial aid, or taking responsibility for applicants and easing their pressure. The influx of Ukrainian refugees has added complexity to the current situation, but new data and visualizations show how to help improve responsibility-sharing and solidarity mechanisms between Member States.

The idea of an “effective system of solidarity and responsibility” is at the heart of the EU’s new asylum pact, designed to overcome years of imbalances between member states. Solidarity will be compulsory under the pact: countries that receive few requests for protection will be able to choose the type of help they give to countries that receive many:

- Relocations of applicants from “overburdened” countries;

- Financial contributions or alternative solidarity measures like staff and in-kind support; and

- “Responsibility offsets”: accepting responsibility for claimants already present in the country but who could be sent back to the country of first arrival under the – still in place – Dublin rules.

The implementation of such a responsibility-sharing mechanism requires a geographical measurement tool and some criteria to determine what would be an equitable distribution or an “overburdened” country.

Different Forms of Protection

Although the redistribution of asylum claims has already been discussed in an earlier nccr – on the move blog post, the war in Ukraine and the activation of the Temporary Protection Directive have complicated the issue and highlighted the need for adapting the current tools. Millions of additional people fleeing Ukraine have been assisted in various EU countries without asylum procedures. Some countries on Europe’s southern borders, such as Cyprus, continue to receive a significant proportion of asylum applications, while other countries, most notably Poland, have been at the forefront of providing temporary protection to Ukrainians.

In order to get a global picture, we have improved our measurement tool to take into account both the asylum applications lodged in each country and the temporary protection status granted. Keeping in mind that the Temporary Protection Status (TPS) is granted at 99% to Ukrainian citizens, whereas other persons seeking protection have to lodge an asylum request.

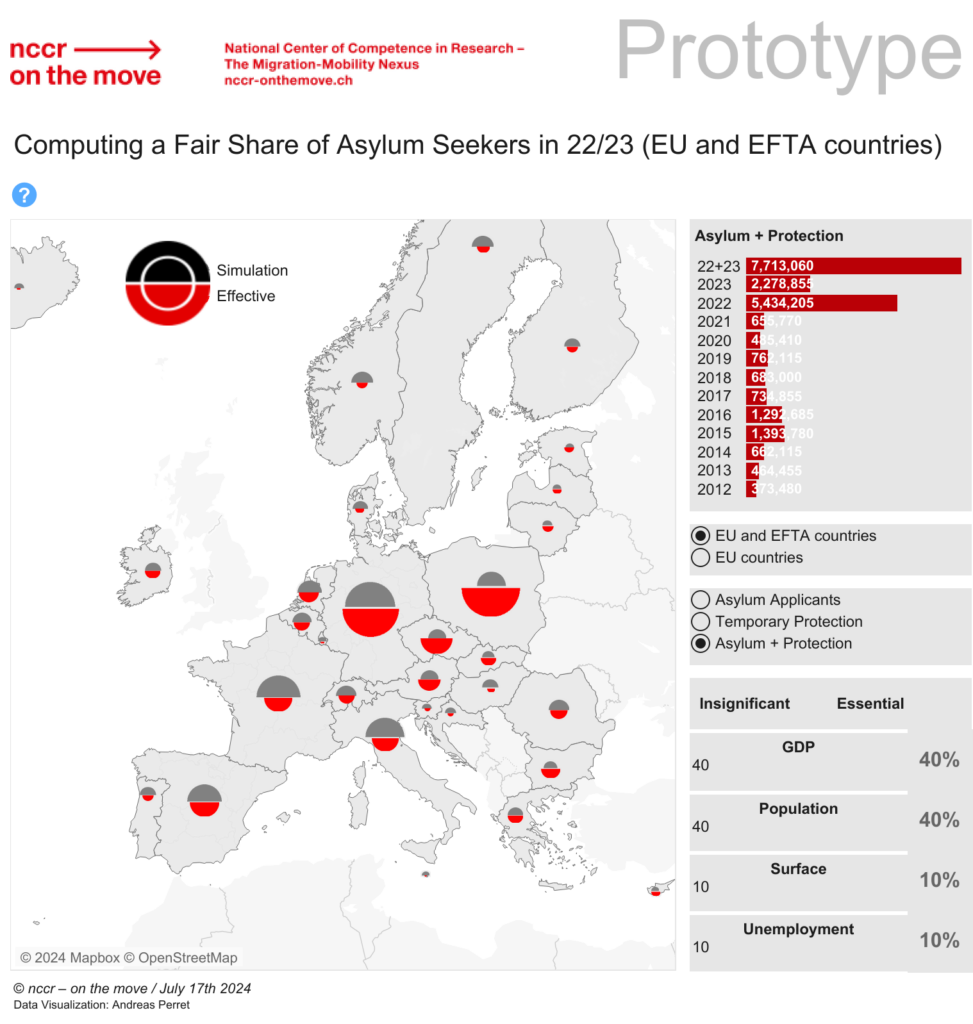

The figure shows that between 2022 and 2023 a total of 7,713,060 persons arrived in EU and EFTA countries either as asylum seekers (2,163,985) or as beneficiaries of temporary protection (5,549,075). The red half-circle on each receiving country shows the actual distribution.

Various Repartition Keys

The strength of our tool is that it allows us to judge according to various combinable criteria if a country receives more or fewer people than it “should.”

The figure above takes the most simple key of population size. That is, according to their population Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Poland and Estonia have been taking in quite a few applicants, whereas Hungary, France, and Italy on the other hand receive relatively few people. Switzerland does exactly its share neither more, nor less…

If a “compromise” key is chosen (e.g. 40% population, 40% GDP, 10% wealth, 10% unemployment), a key conclusion is that the imbalances remain quite small at the level of the EU as a whole. Many eastern countries, which would have to make considerable efforts to correct the imbalances regarding asylum seekers, are now in a much more balanced position. This probably explains why the initially very controversial EU Pact was eventually accepted by these countries.

The interest of our tool is that it does not decide what is ‘fair,’ but provides factual data for informed discussion and negotiation. It makes it possible to consider the two populations of asylum seekers and beneficiaries of temporary protection either separately or together and to determine the most appropriate mix among different criteria such as population, surface area, GDP, and unemployment.

Our tool is therefore a major step forward in assessing the geography of protection as a whole and improving reception systems. The next step would be to take into account the number of long-term permits finally granted to people seeking protection. However, this would not significantly alter the results presented here.

What About Switzerland?

Although not a member of the EU, Switzerland is associated with many aspects of the EU asylum policy including Dublin and Schengen. In August 2024, the Federal Council decided that Switzerland should be associated to the new EU Pact.

The S permit for people in need of protection is to a large extent comparable with the Temporary Protection in the EU and is counted as such in our statistics.

If a “compromise” key is chosen to implement the pact and if the future arrivals remain at the current level, Switzerland – considering its impressive GDP, would have to increase its solidarity a little, but the effort would remain fairly modest. The cost of not joining the EU Pact would be much higher, as many more spontaneous applications for protection could be made in Switzerland, without the benefit of shared responsibility.

Etienne Piguet is a Professor of Geography at the University of Neuchâtel and was a Project Leader of the nccr – on the move’s research project on Migrant Entrepreneurship.

Please refer to my 2019 Blog for a Step-by-step example to create a map.