Between Market Power and Labor Rights

Switzerland’s seasonal worker statute – abolished in 2002, tied residence permits to employers. According to theory, such regulation gives employers greater bargaining power in wage-setting and could lower wages. Strengthening immigrants’ social and economic rights through the Agreement on the Free Movement of People (AFMP) may have helped reduce the pay gap between Swiss and foreign workers.

Temporary work visas have a long tradition in many countries as a means of addressing labor shortages. For decades, Switzerland also had a well-established system for recruiting workers for specific sectors and regions that were unable to meet their needs domestically over certain periods of time.

While the exact nature of such “guest worker” programs varies from country to country, temporary work visas are typically tied to a specific job. This makes it more difficult to change employers and often entails the risk of losing the residence permit. This institutional restriction on labor market mobility weakens workers’ bargaining position and gives firms market power.

In labor market research, this phenomenon is known as monopsony power. In the context of “guest worker” programs, it is argued that such power weakens the bargaining position of workers and may therefore encourage discrimination and wage dumping (Norlander, 2021). This criticism is not new. Human rights organizations, left-wing parties and trade unions, as well as (former) seasonal workers themselves, have long criticized “guest worker” programs for their harsh conditions (Mahnig & Piguet, 2003).

The seasonal worker statute in Switzerland was abolished in 2002 with the introduction of the Agreement on the Free Movement of People (AFMP) – partly in response to this criticism. However, “guest worker” programs continue to exist in countries such as Spain, where Moroccan mothers are specifically recruited as harvest workers (Glass et al., 2014). In Switzerland, too, calls for a reintroduction of the seasonal worker permit occasionally resurface.

How Did the Abolition of the Seasonal Worker Status Affect Wages?

The labor market mobility of workers with a seasonal permit was severely restricted, which limited their bargaining power with employers. Under the AFMP, seasonally employed migrants receive a short-term permit and have the right to geographic and occupational mobility. This has shifted the balance of power in favor of workers.

According to the monopsony theory, it is therefore to be expected that the wages of seasonal or temporary migrants have increased since 2002. One way to analyze this hypothesis is to examine the wage gap between workers with a seasonal or short-term permit and workers with Swiss citizenship before and after the introduction of the AFMP in 2002.

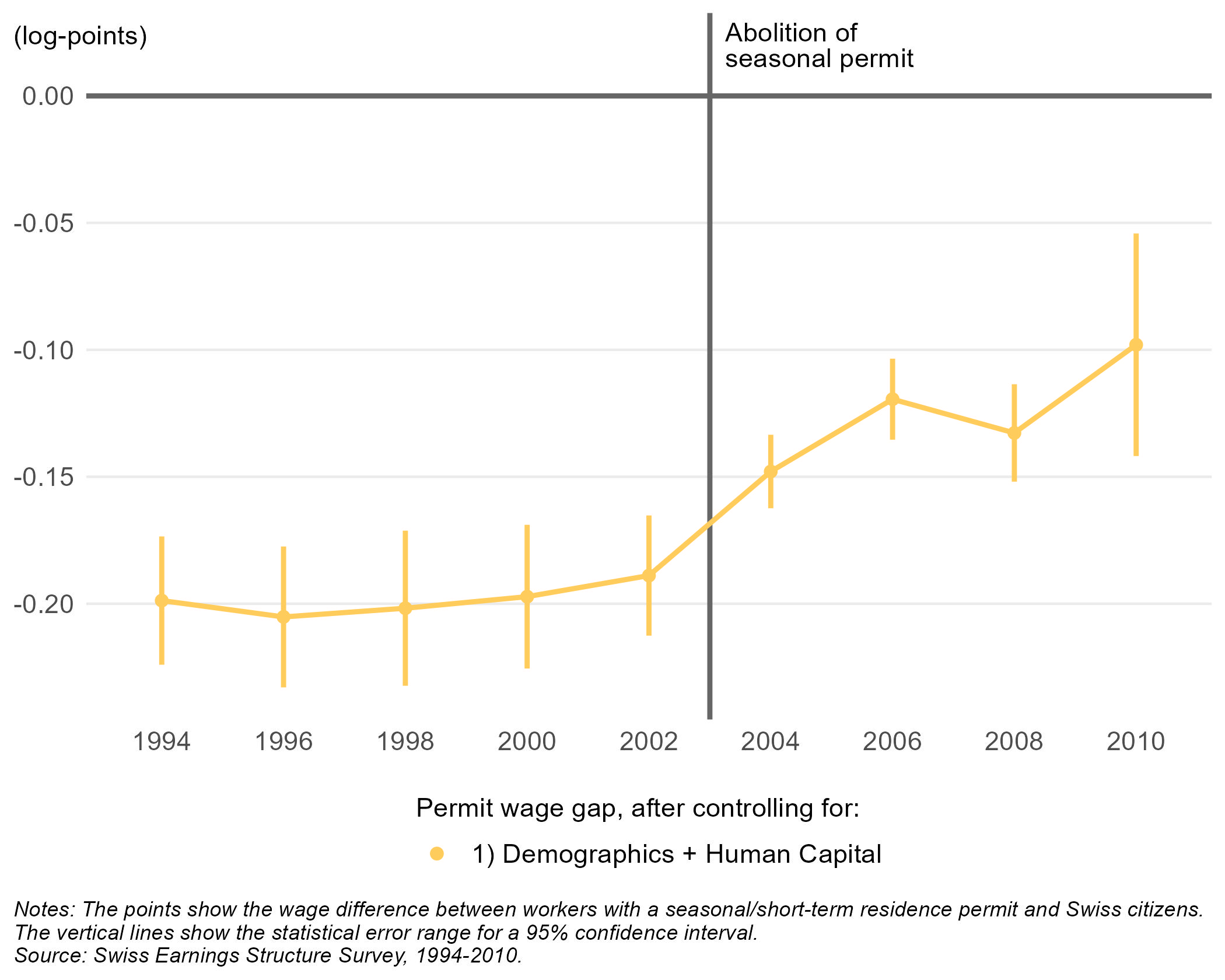

Figure 1.

As seen in Figure 1, in 1994, the wages of seasonal workers were about 20 percent lower than those of Swiss workers with similar demographics, education, and work experience. Controlling for these factors is important because they are known to be relevant for wage determination and because workers with a seasonal permit were on average younger and less well educated than Swiss citizens.

Following the abolition of the seasonal worker statute, the wage gap narrowed considerably, down to 10 percent in 2010. However, the AFMP has also changed the type of jobs in which (temporary) migrant workers are employed. It may be that changes in the composition of migrants can explain the decline in the wage gap after 2002. If this is not the case, it can be taken as an indication that the AFMP’s strengthening of migrants’ rights has enabled them to successfully demand higher wages.

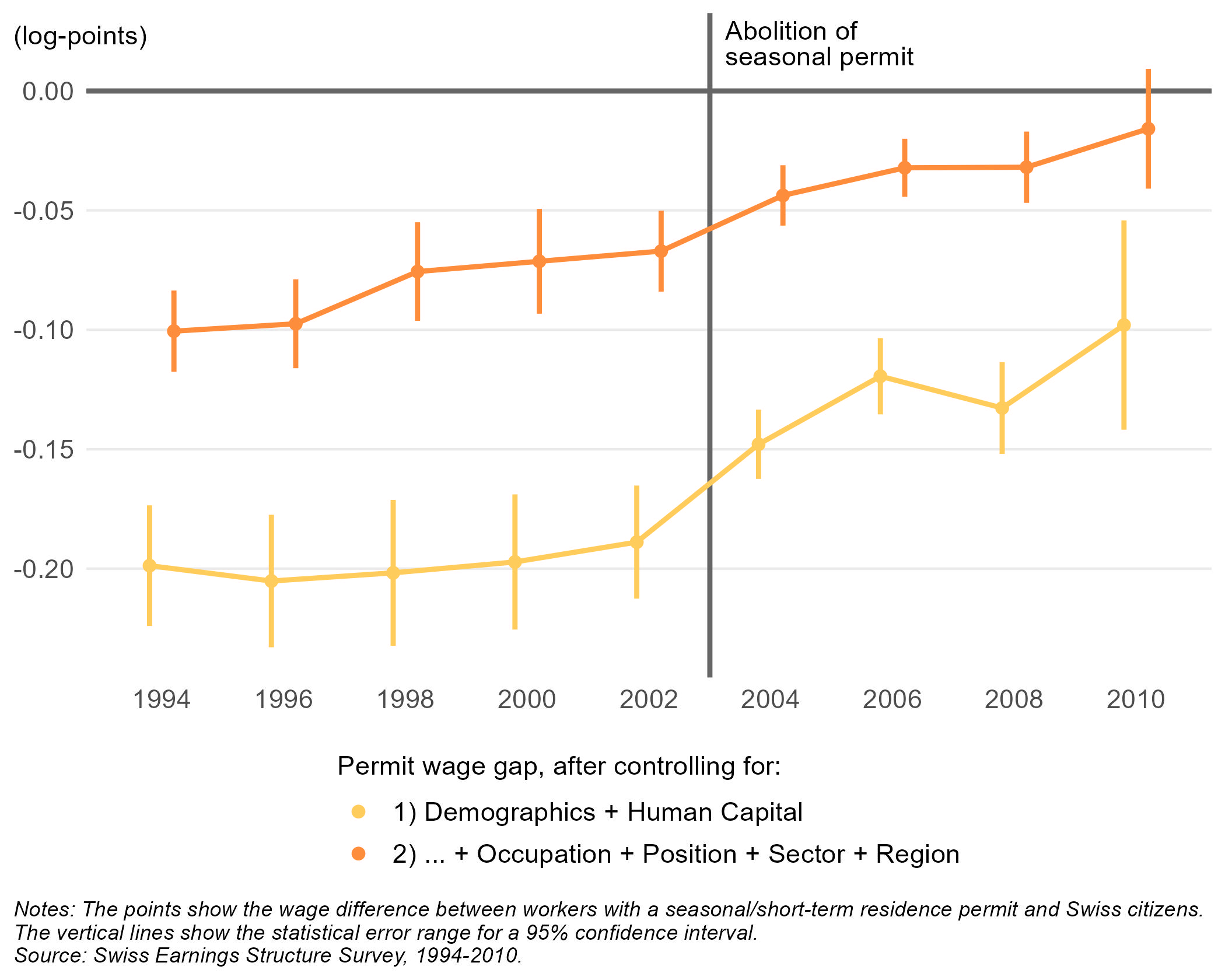

Figure 2 shows the wage gap after controlling for the occupation, professional position, and the employer’s sector and region. Since seasonal workers were often employed in low-wage occupations and sectors, the wage gap before 2002 fell to between 7 and 10 percent. After 2002, workers with short-term residence permits were increasingly employed in higher-paid occupations and sectors, which is reflected in a smaller reduction in the wage gap compared to Figure 1. This suggests that changes in the composition of occupations and sectors can explain some, but not all, of the decline in the wage gap.

Figure 2.

Has the Seasonal Worker Status Trapped Workers in Low-Wage Firms?

The labor mobility restrictions may not only have hindered workers from negotiating higher wages with their current employer, but also moving to higher-wage firms. If seasonal workers had the same chance of being employed by a high-wage firm as Swiss workers, then controlling for the individual effect on wages should not change the wage gap.

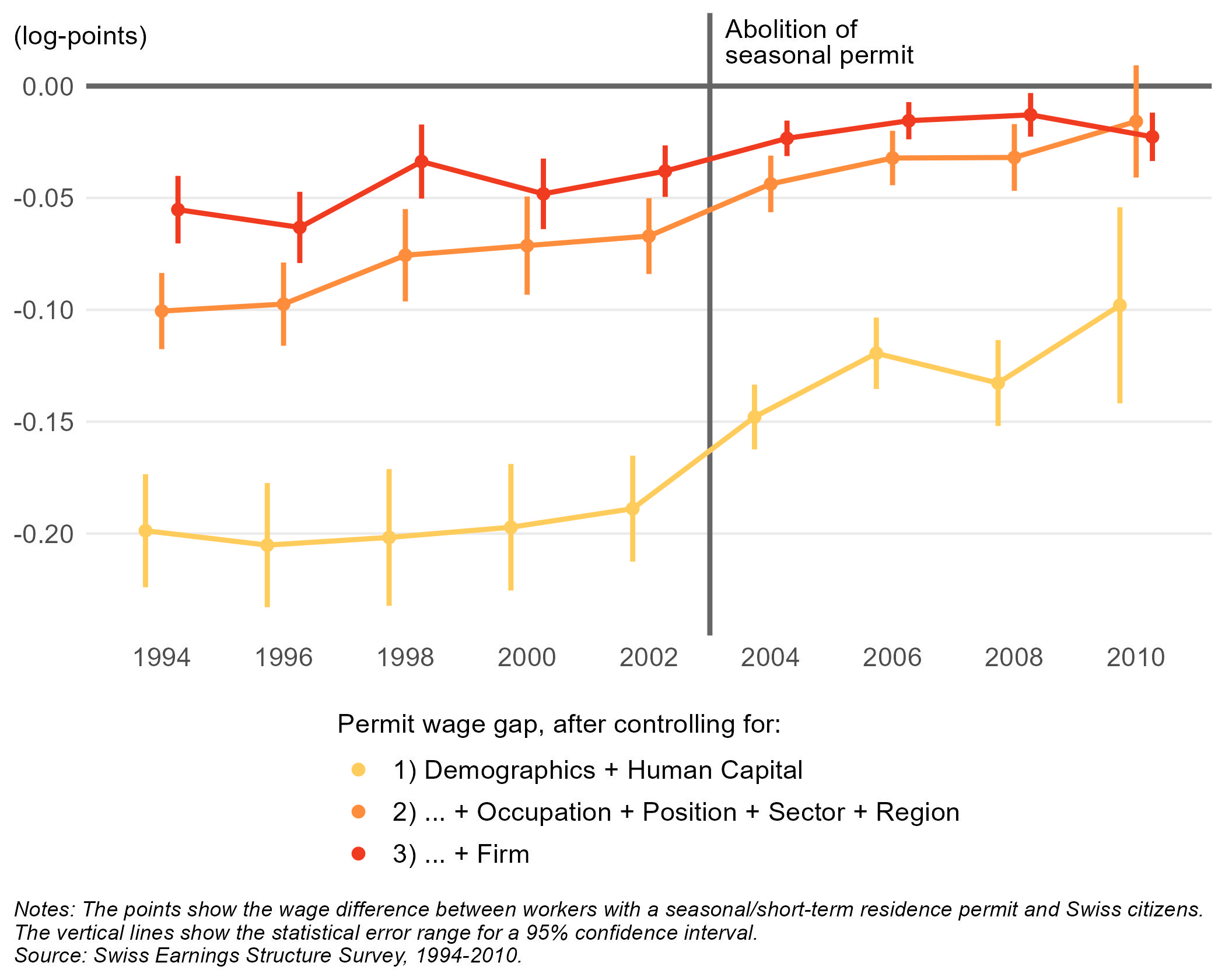

Figure 3.

However, Figure 3 shows that controlling for the firm further reduces the wage gap before 2002. This could be interpreted as meaning that seasonal workers within a sector were more likely to work in low-wage firms while Swiss workers were more likely to work in high-wage firms. However, this does not seem to be the case after 2002. This would imply that newly arrived short-term residents not only increasingly worked in other sectors and in better-paid positions but also found their way into better-paying firms.

The unexplained wage gap between workers with short-term residence permits and Swiss citizens is significantly smaller after 2002 than the wage gap between workers with seasonal permits and Swiss citizens before. These results suggest that the wages of these migrants were too low relative to their labor productivity and that the strengthening of their rights after the introduction of the AFMP helped to reduce the wage gap. The results are consistent with recent studies of “guest worker” programs, which show that tying residence status to employers poses the risk of undercutting wages.

This article has been adapted from its original form and is based on: Schüpbach, Kristina (2023): Zwischen Marktmacht und Arbeitsrechten: Die Auswirkungen des Saisonnierstatuts für die Löhne von Migrant:innen. KOF Analysen, vol. 2023: no. 3, Zurich: KOF Swiss Economic Institute, ETH Zurich, 2023.

Kristina Schüpbach is currently pursuing her PhD at the Swiss Economic Institute at ETH Zurich and at the Immigration Policy Lab. Her research interests include labor economics, migration, and wage inequality. She contributes to the nccr – on the move project ” Ethnic Hiring Discrimination in Times of Crisis.”

References:

–Glass, C. M., Mannon, S., & Petrzelka, P. (2014). Good mothers as guest workers. International Journal of Sociology, 44(3), 8–22.

–Mahnig, H., & Piguet, E. (2003). Die Immigrationspolitik der Schweiz von 1948 bis 1998. In H.-R. Wicker, R. Fibbi, & W. Haug (Hrsg.), Migration und die Schweiz. Ergebnisse des Nationalen Forschungsprogramms «Migration und interkulturelle Beziehungen» (S. 65–108). Seismo Verlag.

–Norlander, P. (2021). Do guest worker programs give firms too much power? IZA World of Labor, 484.