Can Elected Politicians Have Two Passports?

On Wednesday, 1 November, Ignazio Cassis formally replaces outgoing federal councilor Didier Burkhalter as the seventh member of the Federal Council of Switzerland. Born to Italian parents in the Swiss canton of Ticino, Cassis gave up his Italian citizenship just weeks before being elected. His decision sparked a heated debate on whether elected politicians should surrender their foreign passports and renounce their dual citizenship, once elected to a post. In Switzerland, there is no legal obligation to do so.

Ignazio Cassis, a member of the Liberal Party of Switzerland (FDP), becomes the seventh Swiss federal councilor on 1 November. Born to Italian parents in Sessa (Lugano) in 1961, Cassis had both Italian and Swiss citizenship, although he acquired the latter only when he turned 15. His election is historical, as he is the first member of the Federal Council not to have had Swiss citizenship at birth.

Cassis could have also been the first member of the Federal Council with dual citizenship, if he hadn’t decided to renounce his Italian passport in the months preceding his election. In the past, Cassis had been under the scrutiny of rival parties for his dual nationality: several members of the Swiss People’s Party (SVP), in particular, had repeatedly questioned his loyalty to Switzerland. In August, Cassis announced that he had decided to give up his Italian citizenship, although he was under no legal obligation to do so. He insisted that it was a personal and spontaneous decision not influenced by any political pressure.

The other main contender for the cabinet post, Geneva-born Pierre Maudet, a double citizen of Switzerland and France himself, declared that he would have been willing to give up his French citizenship if necessary. While stressing that having dual citizenship did not make him or the 900 000 Swiss who also hold a second passport second-class citizens, Maudet conceded that “if the cabinet were to deem that this caused a problem, especially if I was to be directing the foreign affairs or defense ministries, I would gladly accept its decision“.

The debate should be of particular interest for the 873 046 Swiss citizens with dual citizenship, who represent 10.7% of the population. One group that was particularly upset by these developments was that of the more than 775 000 Swiss living abroad, the vast majority of whom (73.5%) have dual nationality. “We regret this decision, for it implies that dual nationals are not fully Swiss,” said Ariane Rustichelli, director of the Organisation of the Swiss Abroad.

What Are the Rules Abroad?

This debate takes place at a time when the issue of bi-national loyalty is emotionally charged. In the United States, where the current narrative pits “globalists” versus “America First”, naturalized citizens cannot be elected to the White House – and the current President, Donald Trump, first rose to international awareness following a row over the birthplace of the previous incumbent, Barack Obama. Many other countries, especially in South America, do not allow naturalized citizens to be elected. In other parts of the world, naturalized citizens can be elected, but they must give up their other citizenship. Such rules have important consequences. In Australia, for instance, after a heated debate that took place during the summer, several members of parliament who held dual citizenship were forced to resign, causing a major political crisis.

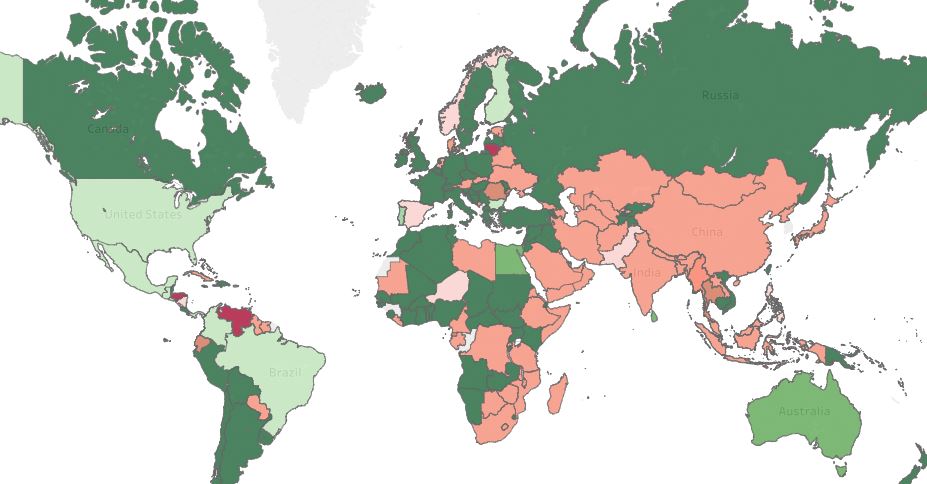

Restrictions based on citizenship for elected politicians: interactive map

Original sources: GLOBALCIT Conditions for Electoral Rights 2015 and MACIMIDE Global Expatriate Dual Citizenship Dataset

The Political Dispute in Switzerland

In Switzerland, the law does not forbid dual citizens to be elected. This issue has already been high on the agenda of the SVP in the past, with the party campaigning for dual citizenship to be forbidden and demanding that naturalized Swiss citizens give up their passport of origin. Both attempts were unsuccessful. However, Ignazio Cassis’ decision to renounce his Italian citizenship was perceived by many as a victory for the SVP. Other politicians have accused the candidates of not resisting to the pressure. “It is pathetic to give up one’s identity,” declared the Christian Democrat Christophe Darbellay. The socialist Ada Marra, herself both Swiss and Italian, said on Twitter that “here are two men who have served their country for years, and now we put them on trial for betrayal?“.

Is it fair to demand of elected politicians to surrender their foreign passports and renounce their dual citizenship? Rainer Bauböck, Professor of Social and Political Theory at the European University Institute in Florence (Italy) and renown expert of citizenship matters, suggests that in situations where there is no legal obligation to give up second citizenship, “renunciation is overshooting: they are elected only for a limited period of time, while renunciation is for life. But in principle, parliamentarians and ministers can be expected to refrain from using a second citizenship, for example by voting in another national election or using citizen privileges in another country. The reason is that elected officials are like trustees or executives on a governing board. While ordinary citizens can have equally strong bonds to two different states and participate in elections there, elected officials have a mandate to represent the citizens of only one state. And this mandate may be incompatible with simultaneously acting as citizens of another state.”

Restrictions to the dual citizenship of elected politicians were initially introduced in times of frequent inter-state wars. These rules reflected ideas of exclusive and blood-based identities. In spite of the fact that the number of countries allowing dual citizenship has risen from forty per cent worldwide in 1960 to over seventy per cent in 2015 (data from The MACIMIDE Global Expatriate Dual Citizenship Dataset), many voters continues to think that politicians with more than one citizenship might not be acting in their best interests. The question remains whether exclusive citizenship is a guarantee for loyalty.

Lorenzo Piccoli

PostDoc, nccr – on the move, University of Neuchatel

On 1 November 2017, Ignazio Cassis will become one of the seven Swiss federal councilors. His election is historical, as Cassis is the first member of the Federal Council not to have had Swiss citizenship at birth and he could have been the first member of the Federal Council with dual citizenship – if he hadn’t decided to renounce his Italian citizenship in the months preceding the election. The nccr – on the move publishes a short series of blog posts reflecting on legal and political questions concerning elected politicians with dual citizenship.