Crisis Communication on Twitter: The Case of Switzerland

In COVID times, one of the challenges of the “new normal” has been to communicate the importance of a set of very unusual and stringent rules that populations must follow to contribute to the preservation of their health and public safety. How did the Swiss government and political elites use social media to inform the population about the changes to be adopted in terms of mobility and persuade them to modify their behaviors?

Arguably the most stringent measures implemented by the Swiss government to control the pandemic are the regulations designed to restrict people’s mobility: enhanced border controls, limitations to internal movement of citizens, and imposition of new social distancing rules. Because these limitations bear a high economic and social cost, the behavior changes they impose can appear overly invasive, non-democratic and threatening to citizens, impeding on their willingness to comply. Given the extent of the crisis and its potentially devastating burden on the public health system, deficiencies in political communication about the importance of these measures bear considerable risks. In such emergencies, effective political communication does not only enhance compliance but is also key to avoiding a politicized health crisis that could be turned into a much larger political crisis.

Effective Crisis Communication

Good crisis communication quickly informs the population about the risk and persuades actors to adapt their behavior to the new situation. The perceived legitimacy of the measures promoted is instrumental to enhance compliance and ensure the stability of the political institutions against disruptive politicization. Legitimacy increases when the message communicated by political actors is timely, frequent, and coherent. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, the health guidance related to mobility seems very straightforward, that is, people are encouraged to avoid any non-essential movement and social contact. However, designing an effective message and coordinating the promotion for something as counter-intuitive and foreign as an economic and social standstill is a tall order for any democratic government, especially one with a long tradition of decentralization, such as Switzerland. So, how did they manage?

Swiss Crisis Communication on Twitter

To tackle this question, we collected tweets posted by Swiss executive and legislative actors and state agencies over the first wave of the pandemic. We identified a total of 377 tweets addressing mobility restrictions by 15 main governmental agents. We first looked for timeliness and frequency, which indicate the speed at which messages are communicated at the onset of the crisis and updated throughout the maintenance phase. Delays in providing information can lead to the perception that sources are not transparent, or to the uncontrolled diffusion of misinformation, which is then hard to contain and correct. We then turned to the coordination between actors. To identify relations between actors, we built information flow networks by coding the referencing (retweets or mentions) between actors. These cooperation networks describe how users help each other in transmitting the information to a common destination. The more actors communicate, the denser the network, the more the message circulates and converges.

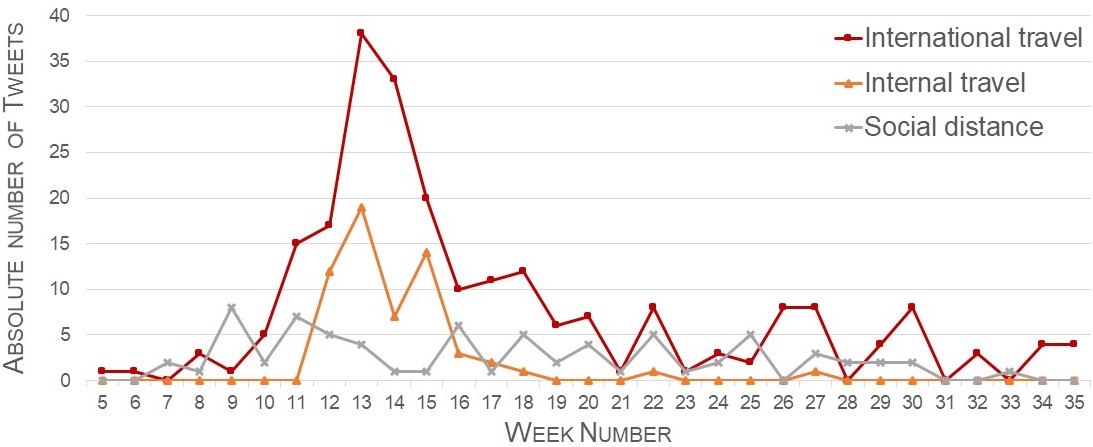

Timeliness and frequency of communication

Despite a satisfactory frequency of messages, the delay in addressing the risk of transmission that comes with human movement might have impeded the legitimacy of the prescribed measures. As shown in Figure 1, the data suggests a surge in communication only when very stringent restrictions linked to the declaration of an “exceptional situation” are taken, without any prior warning. Such severe measures could appear overwhelming to a population, who had been little informed about the risk posed by the virus. That sluggish early communication pace persisted for weeks, even as Italy had already declared a state of emergency as early as January 31st, and as the United States was announcing travel bans for China and European countries. In terms of time-distribution, the lack of sustained communication during the peak of the crisis demonstrated a withdrawal from the issue at odds with the health recommendations to limit mobility, and created a void of information easily filled by misinformation, especially on social media.

Figure 1: Distribution of Tweets on Mobility Issues by Type Through Time

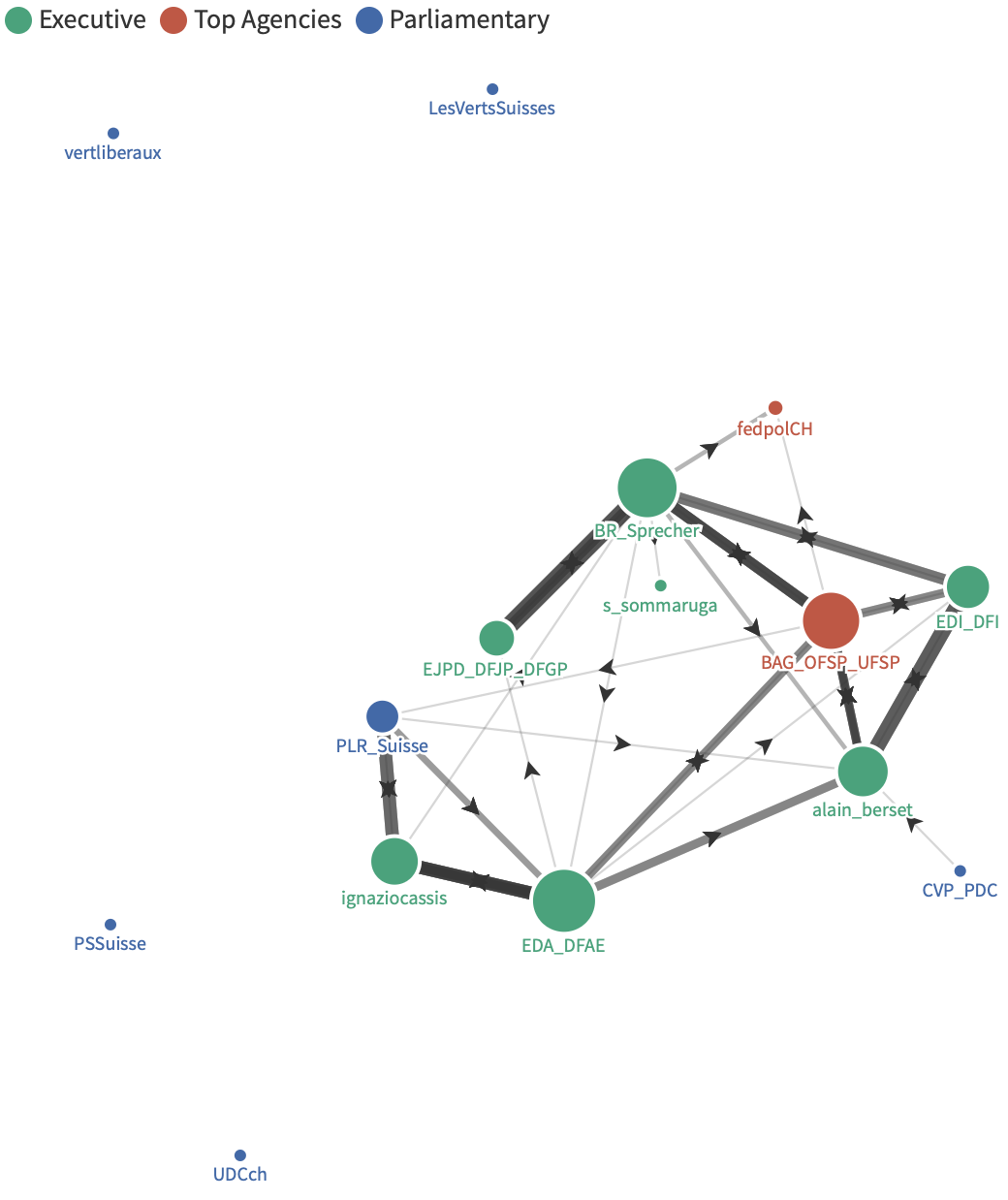

Cooperation Networks

Figure 2 illustrates the cooperation network on mobility issues. The direction of the information flow is represented by the arrows. The most central and connected actors are the department of Foreign Affairs, the Federal Council and the Federal office for Public Health (FOPH). It is interesting to note that a few key actors of the sample remain completely outside of the network; four of the six political parties are never mentioned nor retweeted. This is problematic when it comes to discursive cooperation and message repetition. The connectivity fracture between the political parties and the governmental entities was almost complete. Overall, the shape of this network underscores how deeply the first wave of the pandemic is an executive moment. The most prominent actors in generating and organizing communication are all top executives, organized around the central health agency. Political parties, on the other hand, stay at the margin of the network, with very little participation in its collaborative development.

Figure 2: Cooperation Network Between Swiss Actors on Mobility Issues

Source: Actor’s analysis illustrated by the online tool Flourish

So, was Swiss crisis communication effective during the first wave of the pandemic? The Twitter data shows mixed results. Although Swiss actors made the effort to communicate almost daily about the pandemic online, early communication delays followed by a long downward trend indicates that communication has been overall uneven and declining through time. Moreover, despite an interesting centrality of non-partisan actors such as the FOPH, most political actors in the network refused to play the social media communication game, which entails active participation in the discourse network. This sends a message of disengagement to the populations, who, lacking the expected political guidance seek information elsewhere and risk being deceived. Social media tools provide an easy, unmediated way to communicate clear and accurate information to the population in real time. At the onset of this health crisis, Swiss institutional actors could have taken better advantage of it.

Marie-Eve Bélanger is a Senior Researcher at the University of Geneva and contributes to the nccr – on the move project The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Bordering Discourses Regarding Migration and Mobility in Europe

Sandra Lavenex is a Professor of European and International Politics at the University of Geneva and Project Leader of the research project The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Bordering Discourses Regarding Migration and Mobility in Europe

Alessandra Stampi-Bombelli 28.01.2021

Great post and interesting results! What does week 0 correspond to in Figure 1? It would be interesting to see also how the message developed and changed in the weeks of the pandemic.

Marie-Eve Bélanger 28.01.2021

> Thanks, indeed some promising early results! There is no “week 0”, but week 1 corresponds to the first week of the year (December 30, 2019 to January 5, 2020). The graph covers the period from January 27th to August 30th. And stay tuned for the longitudinal analysis…!