Defunding UNRWA: What Is at Stake?

The Swiss lower chamber made headlines in September 2024 with its vote to suspend Swiss donations to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian refugees, UNRWA. A month later, the Israeli parliament voted to effectively prevent the UN agency from continuing its mandate in Gaza and the West Bank from early 2025 onwards. While the Swiss upper chamber is set to confirm or reject its decision, defunding UNRWA at this critical moment would not only weaken the agency’s finances but also further damage its legitimacy.

In October 2024, the Israeli parliament Knesset voted to effectively bar UNRWA from operating on Israeli territory and forbid Israeli authorities from having any interaction with the UN agency. Despite an international outcry in light of the potentially devastating humanitarian consequences for the population in Gaza, the Israeli government has since then reaffirmed its will to implement these laws that are foreseen to enter into force in early 2025.

In September, the lower house of the Swiss parliament adopted as well three motions related to this UN agency: one to stop Swiss funding for UNRWA immediately, a second one seeking to reform UNRWA, and a third one to redirect the foreseen funding to directly support the Palestinian people without UNRWA involvement.

These parliamentary decisions by Israel and Switzerland came after a summary of an Israeli intelligence dossier was shared with international media, suggesting that UNRWA staff were involved in the terrorist attacks of October 7th, and some 10% of staff members had links to Hamas or the Palestine Islamic Jihad. As a consequence, key donor states like the US, the UK, and the EU temporarily suspended their donations.

A subsequently launched independent review group appointed by the UN secretary-general recognizes in its report that UNRWA has established policies and procedures to ensure the principle of neutrality but also identified measures for facing existing neutrality challenges. An investigation by the Office of Internal Oversight Services found that in nine cases UNRWA workers, whose employment were subsequently terminated, “may have been involved” in the attacks. However, neither of the investigations did prove the involvement of UNRWA workers in the attacks or backed the allegations of a widespread connection between UNRWA and Hamas. In response, all other donor states, except for the United States, have by now resumed their contributions.

While the final decision of the Swiss parliament on defunding UNRWA has not yet been taken, the parliamentary commission of the upper house has postponed their vote on the matter, citing the recent Israeli laws and invoking the need to hold auditions with key actors before taking a decision. The Swiss parliament will have to decide whether it will align with the Knesset’s objective of ceasing the operation of UNRWA or continue its funding in line with other European democracies. The timing of the final decision by the Swiss parliament is now uncertain, given that UNRWA could cease its activities in January 2025 if the Knesset’s legislation is implemented. But what would be the consequences of the decision to revoke Swiss funding for UNRWA?

Financial Effects and UNRWA Funding

The immediate and direct consequence of defunding would be financial. The UNRWA relies on a funding structure that is highly vulnerable to policy swings by donor states and public perception. The agency’s budget depends almost entirely on voluntary contributions by states (95 % in 2022), with more than half of these donations being renewed on a year-to-year basis. This funding structure may explain why, after the withdrawal of several major donors at the beginning of the year, the agency declared that it would have to cease all activities within one month.

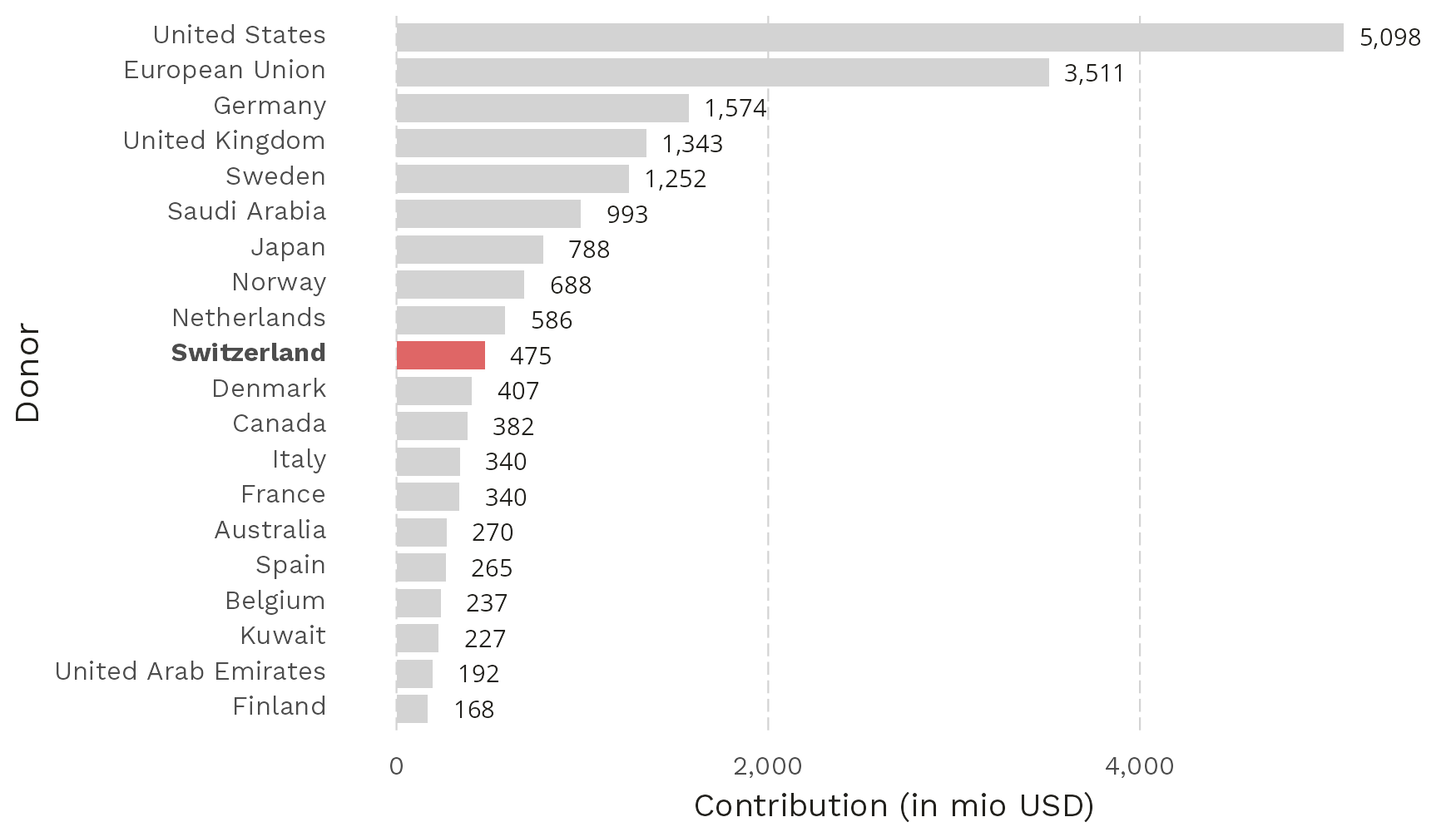

Switzerland has historically been an important contributor to UNRWA. Since the 1950s, the Swiss Confederation has provided contributions in cash and in-kind to the organization, recognizing the agency’s humanitarian role in the region. From 1990 to 2022, the Swiss contributions represent on average 2.5% of the total state donations, reaching around USD 25 million in 2022. As a result, Switzerland ranks as the 10th largest donor worldwide when looking at the sum of contributions since 1990, ahead of countries like France, Spain, and Italy.

Figure 1: Total donations to UNRWA (top 20 donors, 1990-2022)

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto · Data: Collection of the authors

Figure 2: State donations by year: Swiss, US and other contributions

Figure: Alix d’Agostino, DeFacto · Data: Collection of the authors

If the Swiss upper chamber confirms the decision to revoke Swiss funding for UNRWA, the immediate effect would be to cut the total UNRWA budget for 2024 by an additional CHF 10 million. However, given that the Swiss Parliament is the first one to consider such a decision after the Knesset’s efforts to effectively ban UNRWA, it may also be a signal to other major donor states to follow the Swiss example. This decision would also come at a critical moment as the incoming Trump administration, representing the main UNRWA donor, already cut funding between 2018 and 2020.

From a Looming Legitimacy Crisis to an Existential Threat

Notwithstanding the financial consequences, the Swiss parliamentary motions effectively question the overall legitimacy of the UN agency. Despite being scrutinized and criticized, UNRWA has so far continued to be entrusted with the protection of Palestinian refugees, being perceived as the only actor capable of doing so. The Swiss parliament’s vote to stop its payments to UNRWA and “reallocate” the funds made available to other organizations (CHF 10 million) would signal a clear policy shift.

The approval of these motions is not without risk for Switzerland’s position and reputation on the international scene. Traditionally considered a credible and generous humanitarian player, and with a Swiss national at the helm of the UNRWA, Switzerland could place itself as a leading actor in efforts to suspend UNRWA funding, with potentially only the incoming Trump administration taking the same position. Moreover, the alternative that is put forward, namely to replace UNRWA with other actors like the UN’s refugee agency UNHCR or the International Committee of the Red Cross, seems unlikely: both organizations have repeatedly declared that they cannot replace the UNRWA in that region.

In any case, charging a different humanitarian player in the region to replace UNRWA is not within the reach of Swiss diplomacy. Since UNRWA has been established by the UN General Assembly, revoking its mandate and replacing it would require another vote in the same forum, where Switzerland may struggle to find like-minded countries. As a result, a unilateral cutting of the funding would be likely to deprive Palestinian refugees of essential humanitarian aid as the proposed alternatives are unrealistic and go against the grain of the international community. Consequently, defunding UNRWA in that manner would also undermine the Swiss humanitarian tradition and its commitment to multilateralism.

Between Humanitarian and Political Crises

Considering the Knesset’s decision to ban its operations and an incoming Trump president who has already proved its disengagement with the UN system in the first term, it is uncertain what upholding the state donations would mean for UNRWA in a time of existential crisis. However, defunding UNRWA by the Swiss parliament would certainly weaken the agency’s finances and legitimacy, and contribute to a development that may effectively terminate the agency’s operational capacity.

*This article was initially published by DeFacto on 2.12.2024 and adapted to fit the nccr – on the move blog platform.

Maud Bachelet is a PhD researcher at the University of Geneva working on the politics of responsibility-sharing in the EU. She is an associated researcher to the nccr – on the move project “The Impact of Crises on the Governance of Migration.”

Philipp Lutz is a senior researcher at the University of Geneva and an assistant professor at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He is an FNS Ambizione grantee for the project “Connecting countries and dividing people: The politics of burden-sharing in times of contested globalization” and an associated researcher of the nccr – on the move project ” The Impact of Crises on the Global Governance of Migration: Boost or Blow.”

Frowin Rausis is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Geneva and an alumnus of the nccr – on the move project “The Mobility of Migration Policies: Pathways and Consequences of the Diffusion of Migration Policies.”

Remark:

The data and plots in this blog piece are the result of a broader data collection effort by the authors on the funding of UN refugee agencies between 1990 and 2022.

References:

Rausis, F., Bachelet, M., & Lutz P. (2024). UN refugee agencies: vulnerable funding structures and a looming legitimacy crisis. Forced Migration Review.