Deported to Mexico as Strangers

More than 100 000 people were deported from the United States to Mexico in 2017. Some of them have been living in the United States as undocumented immigrants for many years. Some of them do not have family connections in Mexico or speak Spanish. What happens once they arrive in Mexico? A visit to a migrant shelter in Tijuana.

In 2017, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement arrested 143 470 people and deported 226 119 people. 128 765 of them were deported to Mexico. People were deported directly after entering the United States or once their jail sentence was over. However, especially since 2017 more and more people were arrested on the street, in their homes, or while waiting in front of schools to pick up their children – with no time to pack or arrange anything.

When they arrive in Mexico, they often do not carry many personal belongings. Some of them have no memories of Mexico, do not speak Spanish, do not have Mexican documents, family ties or other connections to the country. In case their families live in the United States and are undocumented it is impossible for the family members to visit each other, since none of them can cross the border unless the ones living in the United States want to settle in Mexico for good.

This situation creates difficulties for families and individuals, and it also creates a situation in Mexico where immigrants and their children have to participate in the job market or school system without any preparation, sometimes without language skills or financial means.

“Casa del Migrante”, a Migrant Shelter in Mexico

(Photo: Katrin Sontag)

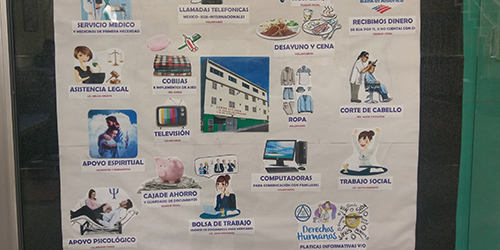

A lot of the people who are deported, are deported to Tijuana, the most North-Western Mexican border city. The “Casa del Migrante”, run by the Scalabrinian Congregation, is one of the shelters in Tijuana that help migrants and deportees find their way. It provides food, shelter and clothing for a limited amount of time. In its 31 years of existence, the center has welcomed around 260 000 people – 90% of which are deportees from the United States. For instance, the night before our visit to the “Casa del Migrante”, 40 new people arrived. The shelter has 140 beds, a storage for clothing and toiletries, and a kitchen. It offers practical, legal, social, and spiritual counseling as well as services such as medical services and hairdressing on particular days of the week. The staff also assists with establishing family contacts or accessing any savings or bank accounts left in the United States. Permanent staff and volunteers from different countries work at the shelter. The “Casa del Migrante” only accommodates men, but there is a separate shelter for women and children in the same street.

(Photo: Katrin Sontag)

Perceived Changes since Obama’s Presidency

More and more, deportees are people who have been living in the United States as undocumented immigrants for a long time, whose children or parents still live in the United States, or who are elderly people. Father Pat Murphy, who runs the “Casa del Migrante”, estimates that the people who have arrived in 2017 spent an average of eleven years in the United States before they were deported. He also observes that five years ago the average age of deportees was between 25–30 and that now also people in their 80s are deported.

Father Pat Murphy, Director of “Casa del Migrante” (on the right), talking to our group of visitors. (Photo: Katrin Sontag)

Yet, even more people were deported in the period of Obama’s presidency than in 2017 (409 849 in the peak year 2012 and 240 255 in 2016). However, the emphasis has shifted from deporting mostly people who were picked up directly after entering the territory and people with criminal records to a stronger enforcement of the laws among people living in the United States as undocumented immigrants. The numbers may increase once the cases of those who are currently in detention will have been processed.

Future Perspectives for the People Concerned

For the people at the “Casa del Migrante”, finding jobs and settling is difficult – especially for those with limited language skills, criminal records, or for elderly people. In addition, the wages are much lower in Mexico than in the United States and it is impossible to provide for a family left over there. An option for English-speaking deportees is to work at one of the call centers set up by U.S. companies or international debt collectors. Other jobs might be found in tourism or language teaching, as a deportees’ guide on the internet advises.

The “Casa del Migrante” aims at helping people to build up a new life and routine quickly rather than remain in a feeling of helplessness for too long after their deportation. This is done through assistance, but also by setting a limit to the stay and establishing a daily routine for everyone staying there.

Katrin Sontag PostDoc, nccr – on the move, University of Basel and visiting fellow in 2018 at the Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, UC San Diego