Football and Citizenship in the 2018 World Cup

Unlike his brother Granit Xhaka, who plays for the Swiss national team, the Basel-born Taulant Xhaka opted to play for Albania, where his parents were born. The two brothers did not play against each other at the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia. If Switzerland would have qualified for the quarterfinals, Xhaka and teammates would have faced Ivan Rakitic with whom they had played in the Swiss youth squads. In 2007, the young Barcelona star joined the Croatia national squad. So, where’s the catch?

Many sportspeople were born in states, under whose flags they compete, but they may as well have migrant parents or ancestors. In terms of nationality laws, this could potentially give them access to dual or multiple nationality. That is a chance to join two or more national teams. However, the eligibility rules of the International Football Federation (FIFA) prompt players to decide on whom they want to represent early on in their careers, already at the age of 21 years. And that choice is a final one: if a player has represented one country even in a single official professional match, he or she will not be able to represent another country ever again (Article 15, FIFA Statute).

Players with dual nationality may base their choice on greater chances of playing at the international level, or simply on the feeling of a stronger emotional attachment to one country over another. The former is arguably the case of Diego Costa, who in 2014 decided to play for Spain, a country where he had just recently obtained nationality, instead of his native Brazil. Costa had erroneously hoped that by playing on the Spanish team (winners of the 2010 World Cup and the 2012 European Championship) he would spend more time in the field and win more awards. Unlike Costa, other players chose emotional bonds over fame, in deciding which team to represent. Kalidou Koulibaly, for instance, played for the French national youth teams before joining Senegal in 2015. Koulibaly’s wife prompted this decision because she convinced him that playing for the African nation would make his “parents proud”.

These choices shape the history and geography of world football. Imagine how past world championships would have looked like if Patrick Viera had chosen to play for Senegal instead of France, John Barnes for Jamaica instead of England, Miroslav Klose and Lukas Podolski for Poland instead of Germany. Even today’s world cup would look very different if Lionel Messi had chosen Spain over Argentina and Kylian Mbappé Cameroon or Algeria over France.

One in Six Players with Migrant Background

With anti-migrant sentiments on the rise in Europe and beyond, few people are aware of the fact that one in six players at this year’s World Cup in Russia has a migrant background, i.e., has been born abroad or has at least one parent of foreign descent. According to the data collected by The Washington Post, 82 out of the 739 players in this year’s World Cup have been born abroad; 22 out of the 32 teams have at least one foreign-born player and Morocco has 17 of them. More than 200 players at the 2018 World Cup have double or multiple nationality (or at least a claim to it) and could have chosen to play for a different team than the one they represent today.

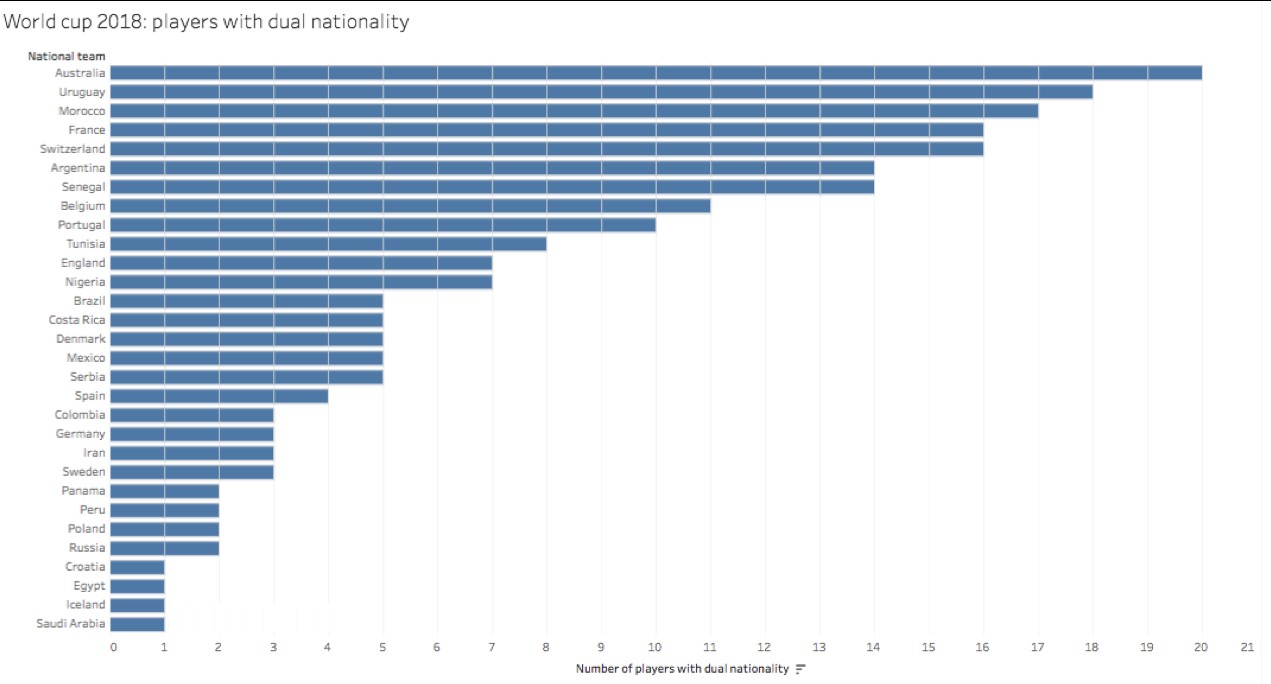

Worldcup 2018: players with dual nationality

Own elaboration; original data from https://www.transfermarkt.com/

The fact that a total of 220 players at the World Cup had dual nationality reveals how global mobility has affected the ways in which citizenship is understood, lived, and regulated around the world. When Belgium and France faced each other in the semifinal, 27 players on the pitch had dual nationality. They were not the only ones: eight Senegal players were born in France; eleven from among the Uruguayan team have Italian nationality. The Swiss national team has players who could have chosen to represent Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Chile, Croatia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ivory Coast, Kosovo, Macedonia and Nigeria. In terms of the applicable laws, but also in the sense of belonging, these players and their families are no longer anchored only in the place where they were born.

Migration flows and evolving citizenship rules have enabled individuals to be at “home” in more than one state. Just as when a footballer sends the ball to an open teammate in a square pass, they may as well opt for allegiance to a passport that opens the doors to new professional or life opportunities.

Lorenzo Piccoli

nccr – on the move, University of Neuchâtel

Jelena Dzankic

European University Institute (EUI), GLOBALCIT

A longer version of this post was originally published on 12 July 2018 on GLOBALCIT and can be read here.