One Size Does Not Fit All – Resilience Profiles of German, Greek and Swiss Pupils

Resilience processes have been studied for many years. Previously the focus was mainly on individual protective factors such as self-esteem and self-efficacy, etc. However, in recent years, research has focused on a multisystemic approach to the concept. Moral values, as well as structural and social dimensions, shape the normative nature of resilience. It seems therefore essential to consider them when designing tailored intervention programs to support students and foster resilience.

Resilience could be described as a bunch of rubber bands. You can stretch it as much as possible, and it will bounce back into its original shape. Psychological resilience seems to be about bouncing back – to be successfully able to adapt despite challenging or threatening life circumstances. It is often mistakenly assumed that resilience is a character trait or attribute you either possess or don’t. Research on resilience has shown that it involves how an individual positively adapts in difficult times and responds to challenges and adversities (Luthar et al., 1997). Furthermore, it can be fostered and built.

But how does one define a rubber band in such a way that also allows us to measure it when conducting research? It is one of the most crucial, yet difficult questions resilience researchers face. A predominant definition of resilience describes it as “the capacity of a system to adapt successfully to disturbances that threaten the viability, function, or development of the system” (Masten 2014). These adversities are often referred to as risk factors (e.g., critical life events, trauma, loss, etc.). In contrast, positive adaptation is achieved through protective and promotive factors (e.g., high self-esteem, supportive family, supportive peers, etc.,).

Masten’s definition is broad enough that it can be applied to diverse systems. Consequently, an individual can be resilient but so can a system. It is scalable across different disciplines and levels of analysis, which is crucial due to the multisystemic nature of resilience. Resilience is more than having high individual protective factors. A supportive family and social environment are just as crucial as personal factors, if not even more critical.

Our Goal

Because resilience is such a multisystemic and highly contextually sensitive concept (Ungar and Theron 2020), it seems important to differentiate the factors and/or processes leading to the different outcomes for each person as well as how the persons are impacted by the levels of risk factors they are exposed to. We chose to investigate the resilience of early adolescents in Germany, Greece, and Switzerland suffering from depression and anxiety symptoms seen as risk factors over time, all the while taking into consideration their protective factors on individual, family, and social environmental levels.

We used a person-centered approach, called latent profile analysis (LPA), a data-driven statistical method grouping heterogeneous samples into homogeneous groups and allowing a view of a person as a system of interacting dimensions. Because it is a data-driven approach, the number of groups and the group sizes varied depending on the investigated samples.

While using a variable-centered approach to studying group differences, we wanted to know whether there were more girls or boys and whether the students were with or without a migration background.

Contextual and Formal Differences in Groups

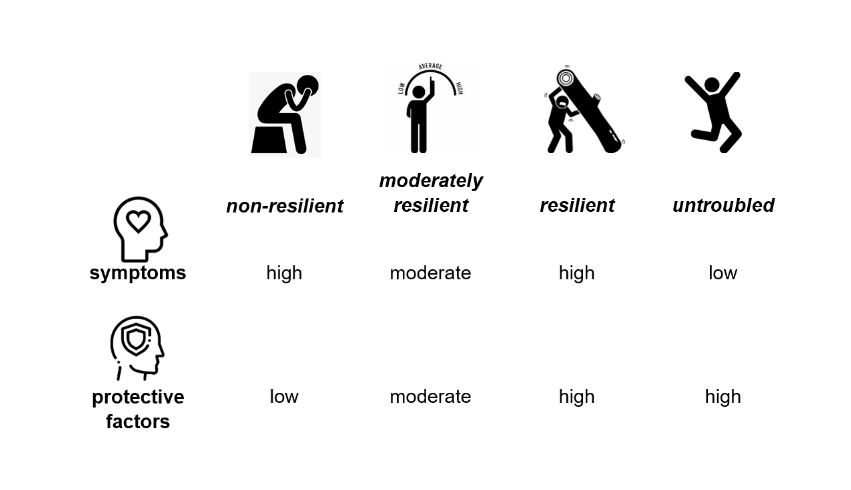

We detected four different groups (see Figure 1). The first profile was characterized by high levels of symptoms (anxiety & depression) and low protective factors (personal competence, social competence, structured style, social resources, family cohesion). We called them the non-resilient students. The second profile included students with moderate symptoms and moderate protective factors, called moderately resilient.

The third profile showed high levels of symptoms and protective factors, this group was called resilient students and finally, the last group with low levels of symptoms and high levels of protective factors was the group of the untroubled. Unfortunately, the levels of individual stress were not included in this analysis.

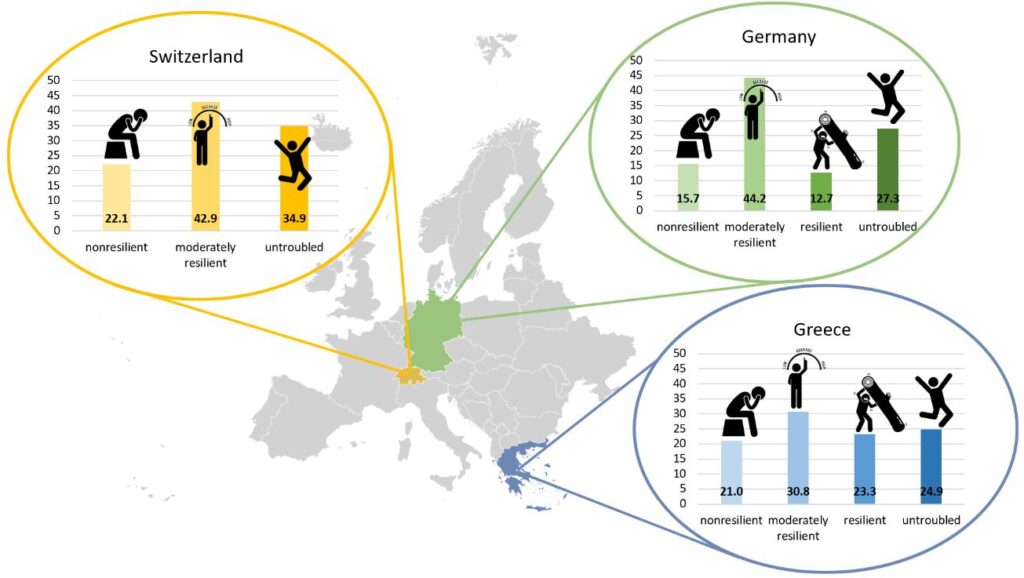

Unsurprisingly, when considering the highly-contextual nature of resilience, we found a different number of groups in the three sample countries (see Figure 2). In Switzerland, we detected three profiles (excluding the resilient profile), whereas four profiles could be found in Germany and Greece. Most students belonged to the moderately resilient group, and the smallest group was the non-resilient in Greece and Switzerland, and the resilient in Germany.

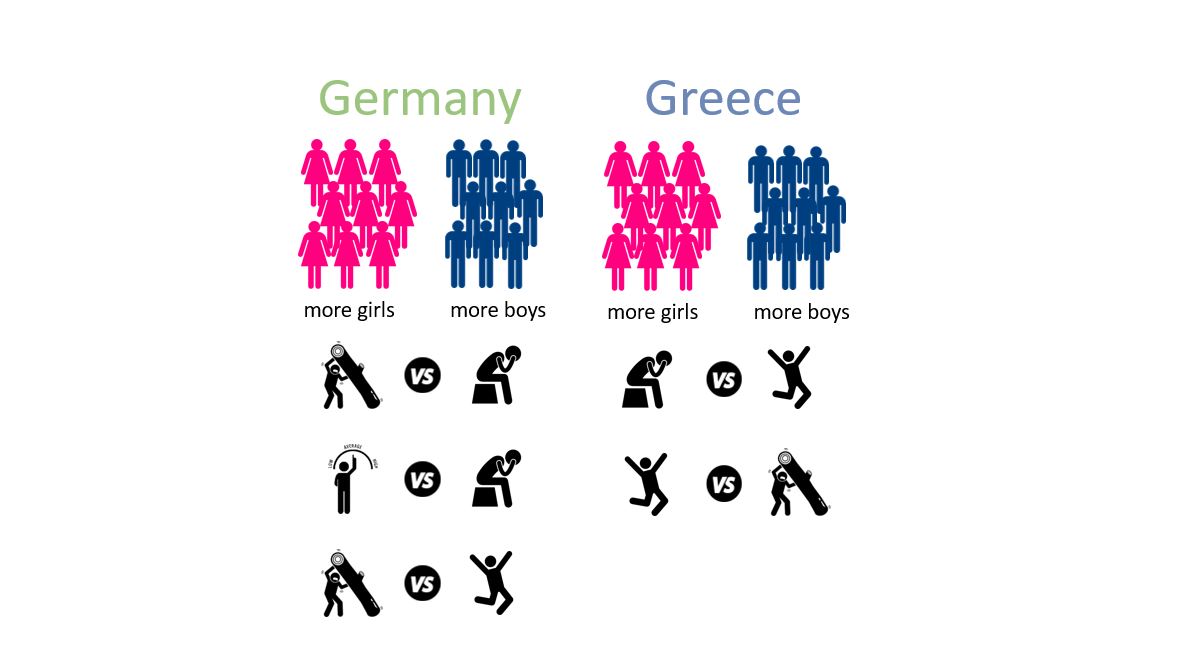

While no group differences were found in the Swiss sample (see Figure 3), girls were more likely to be in the resilient or moderately resilient profiles compared to the non-resilient profile in the German sample (and vice versa for boys). It is therefore more likely to find more girls in the resilient and moderately resilient profiles when comparing them to the non-resilient profile. Also, they were more likely to be part of the resilient profile compared to the untroubled.

In the Greek data, girls were more likely to be part of the non-resilient profile compared to the untroubled. However, they were more likely to be part of the untroubled than the resilient profile (see Figure 2).

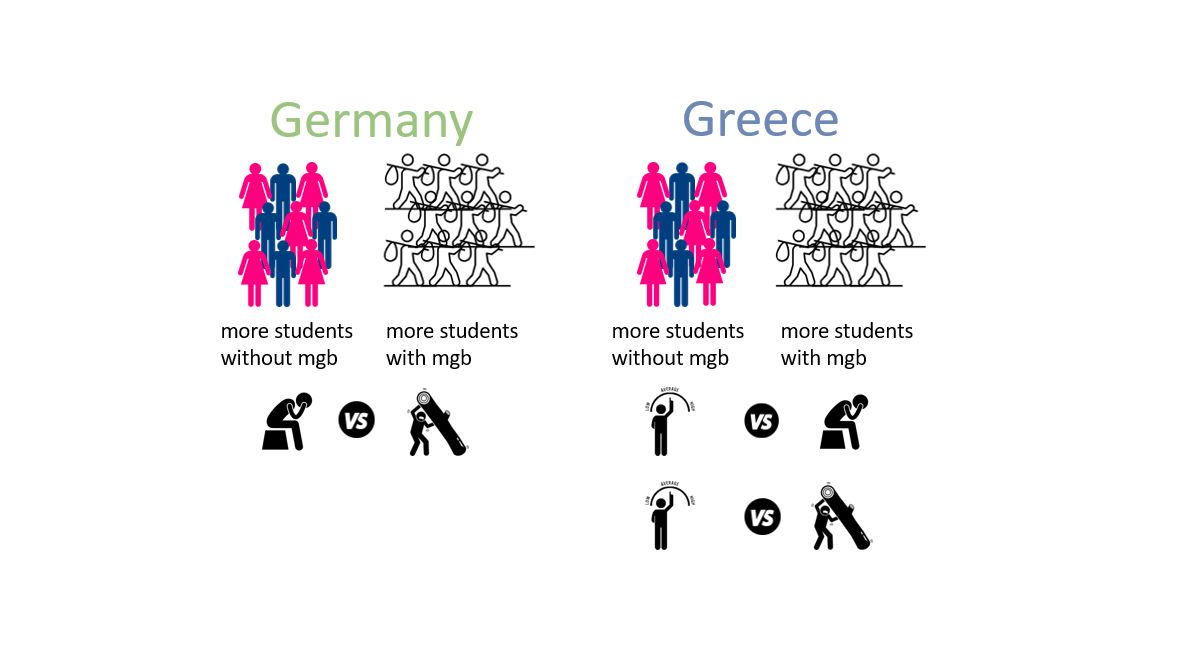

Figure 3  Furthermore, students without a migration background were more likely to be part of the non-resilient group than the resilient one in Germany (and vice versa for students with a migration background). In the Greek sample, students without a migration background were more likely to be part of the moderately resilient group than the non-resilient and resilient groups (see Figure 4).

Furthermore, students without a migration background were more likely to be part of the non-resilient group than the resilient one in Germany (and vice versa for students with a migration background). In the Greek sample, students without a migration background were more likely to be part of the moderately resilient group than the non-resilient and resilient groups (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 Tailored Programs to Support Resilience

Tailored Programs to Support Resilience

These findings demonstrate the context sensitivity of resilience. It does not mean that there are no resilient students in Switzerland nor that all girls/boys and students with/without migration backgrounds are entirely similar. However, the German and Greek datasets resulted in more nuanced profiles.

Most importantly, it reminds us to consider all information available when drawing conclusions regarding resilience. Having high levels of symptoms does not automatically mean that protective factors are missing. Some students might not know how and when to use them. We cannot assume that all girls and boys and students with or without a migration background have the same needs. Therefore, more tailored intervention and prevention programs are necessary to support students and foster their resilience.

Clarissa Janousch is a doctoral student at the FHNW School of Education and at the University of Zurich in the project nccr – on the move Overcoming Inequalities with Education. Her areas of interest are psychosocial processes leading to positive adaptation and mental health.

References:

–Janousch, C., Anyan, F., Kassis, W., Morote, R., Hjemdal, O., Sidler, P., Graf, U., Rietz, C., Chouvati, R., & Govaris, C. (2022). Resilience profiles across context: A latent profile analysis in a German, Greek, and Swiss sample of adolescents. PLOS ONE, 17(1), e0263089.

–Luthar, S. S., Burack, J. A., Cicchetti, D., & Weisz, J. R. (1997). Developmental psychopathology. Cambridge, UK.

–Masten, A. S. (2014). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. Guilford Publications.

–Ungar, M., & Theron, L. (2020). Resilience and mental health: How multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(5), 441-448.