Precarious Work in Switzerland: Experiences of Crises of a Hospitality Worker

Low wages, limited access to social protection and benefits, temporary or seasonal labor contracts, and employment through recruitment agencies or subcontractors are all defining characteristics of precarious work. The COVID-19 pandemic – marked by constant uncertainty and rapid change – has exacerbated precarious working conditions for many, especially for migrants. Insights from Fransisca’s* personal experiences highlight the impact of these challenges.

In a report on combating precarious employment, the ILO (2011) states that “[w]hile the increase in insecurity in employment is ubiquitous, its extent, meaning and impacts remain subject to much debate as there are no agreed official definitions.” However, the same report identifies four key characteristics of precarious work: low wages, poor protection against termination of employment, lack of access to social protection and benefits, and limited opportunities to exercise workers’ rights. These characteristics are particularly prevalent in employment relationships that are of limited duration or are de-standardized (ILO, 2011).

The Hospitality and Catering Industry

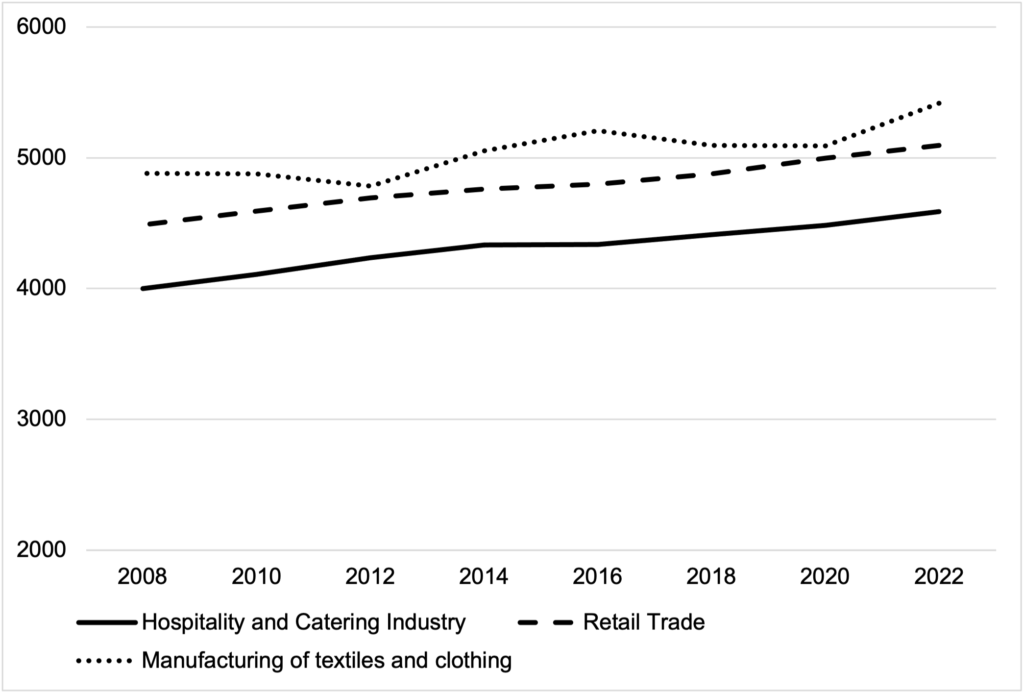

The hospitality and catering industry stands out as a sector where precarious work is particularly evident. Indeed, all four characteristics of precarious work identified by the ILO (2011) are present in this industry, with low wages being especially notable. As Figure 1 shows, the hospitality and catering industry belongs to the three industry sectors in Switzerland with the lowest wages, with an average gross salary of only 4587 CHF per month in 2022.

Figure 1: Evolution of Monthly Salary of Industry Sectors in Switzerland with Lowest Monthly Gross Salary [in CHF].

Source: Swiss Earnings Structure Survey (ESS), own calculations.

In addition, workers in this sector face unpaid overtime, long and anti-social working hours, harassment, and bullying. There is also a high share of part-time, casual or seasonal employment (Alberti, 2014; Robinson et al., 2019). For migrant workers – who constitute a substantial proportion of the labor force in this sector in Switzerland – there is the added vulnerability of being dependent on their employer to maintain their legal status (Alberti & Danaj, 2017).

The COVID-19 Pandemic

During the pandemic, these precarious working conditions were further exacerbated: constantly changing safety measures and heightened uncertainty intensified the challenges faced by workers in the hospitality and catering industry. The comprehensive chronicle of the pandemic compiled by the Swiss Tourism Federation vividly illustrates how the sector, its businesses and employees were forced to adapt to the crisis – sometimes ceasing work entirely to prevent further infections. But how did this impact the situation of labor migrants?

Financial Repercussion

During the qualitative interviews conducted as part of the NCCR project “Evolving (Im)Mobility Regimes” financial consequences of the pandemic played an important role. This is hardly surprising, given that short-time work was implemented in this low-wage sector for several months in 2020 and 2021. During these periods, employees received only 80% of their usual salary.

This financial precarity was further exacerbated by seasonal employment contracts, particularly for participants who remained in Switzerland during the off-season but did not register with unemployment insurance, despite being eligible. In such cases, workers often stretched their 10 monthly salaries to cover their expenses throughout the entire year.

For some participants of our study, the combination of low wages, loss of income during the off-season and reduced earnings due to short-time work during the COVID-19 pandemic meant that they struggled increasingly to make ends meet at the end of each month.

Navigating Financial Uncertainties

Fransisca, a Portuguese woman in her mid-forties employed seasonally as a housekeeper in a hotel in the canton of Wallis/Valais, illustrates this situation. Despite the seasonal nature of her work, she has lived in Switzerland for over 20 years.

When asked about her current, post-pandemic, financial situation, Fransisca explained: “There are months when I’m fine and others when I struggle. […] For example, I left a hotel where I earned CHF 3500 and came here, where I earn CHF 3100. It’s a big difference.”

Her financial situation before the pandemic was similarly precarious. However, when the pandemic broke out, her circumstances worsened, prompting her to register with the unemployment insurance fund: “I applied for unemployment benefits. I had to send emails using the computer, well not me, my partner had to do it, and we wrote about the jobs I didn’t have.” Whenever possible, her employer at the time offered her work: “I cleaned the apartment and earned CHF 150. […] The unemployment benefits covered what my boss couldn’t pay me.”

Interestingly, the financial strain caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, combined with the uncertain duration of the crisis, led Fransisca to register with the unemployment insurance fund. This decision ultimately allowed her to stabilize, and even improve, her financial situation: “I didn’t have any difficulties [during the pandemic]. In fact, it seems like I face more challenges during a ‘normal’ year. For example, when I’m at home for almost a month [during the off-season] and don’t earn anything.”

Unfortunately, this temporary improvement was not sustainable. At the time of the interview in spring 2024, Fransisca had no income due to the off-season. Despite being eligible, she decided not to apply for unemployment benefits, as she found the process “so much work.”

Inequalities in Financial Vulnerabilities

Fransisca’s example highlights the impact that times of crisis can have on already precarious employment. Her financial situation worsened at the outbreak of the pandemic. In an effort to mitigate this additional strain, she eventually decided to register with her canton’s unemployment insurance fund. However, this experience also made her aware of the extensive administrative work involved in such registrations, leading her to forgo applying for unemployment benefits during off-seasons.

While Fransisca was the only study participant who chose to seek unemployment benefits in response to the financial hardships brought on by the health crisis, narratives of severe financial precarity were especially common among the interviewed housekeepers, but less present in the accounts of receptionists, cooks, and pastry chefs. Factors such as education level, gender, and country of origin (EU/EFTA / ‘third country’) played a significant role in shaping these precarity-related narratives.

*For identity protection, the names of participants were anonymized.

Livia Tomás is a Postdoctoral Researcher at ZHAW of Social Work. In the framework of the project “Evolving (Im)Mobility Regimes”, she studies the living and working conditions of migrants in the Swiss hospitality industry and examines how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced these conditions.

Sarah Ludwig-Dehm is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland. Her research interests include international migration, social inequality, and segregation.

References

–Alberti, G. (2014). Mobility strategies, ‘mobility differentials’ and ‘transnational exit’: the experiences of precarious migrants in London’s hospitality jobs. Work, employment and society, 28(6), 865-881.

–Alberti, G., & Danaj, S. (2017). Posting and agency work in British construction and hospitality: the role of regulation in differentiating the experiences of migrants. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(21), 3065-3088.

–ILO, International Labour Organization. (2011). Policies and regulations to combat precarious employment. International Labour Organization.

–Robinson, R., Martins, A., Solnet, D., & Baum, T. (2019). Sustaining precarity: critically examining tourism and employment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1008-1025.

This article is part of a series on “Vulnerabilization of migrant workers during crises.”