Why Discrimination is a Universal Issue

In terms of its societal functioning, one could argue that Switzerland is a failed state, because we didn’t manage to put merit over prejudice. Every day, we, as a society, are at the same time victims and perpetrators of discrimination. It’s a complex topic, but one thing is for sure: discrimination is not only detrimental for the victims, but also for social cohesion, the economy, and, eventually, for the perpetrators themselves. Therefore, discrimination is a universal issue and right now we are all on the losing end.

But let us start at the beginning of this mess. Imagine one of these days in the office when you do anything but work. You start skimming through brochures for summer vacations. You will probably end up with dozens of beautiful places around the world where you would want to spend your deserved vacation. It doesn’t make a difference whether it is three, ten, or one hundred places that you like, as long as you don’t have to choose one. Once you have to pick a destination, it gets tricky.

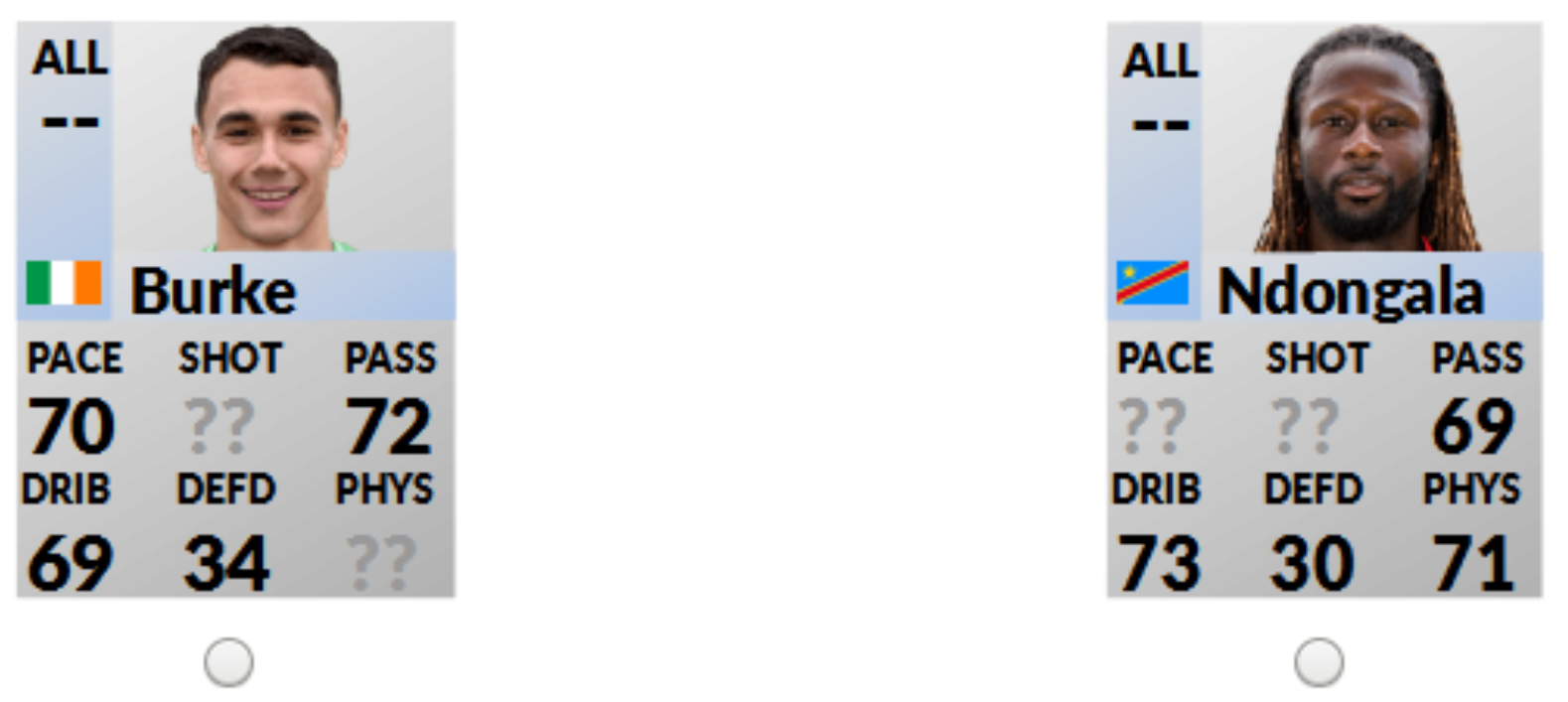

With discrimination, it is similar. In a recent experiment together with Didier Ruedin and Thomas Tichelbäcker, we asked random people to rate the quality of football players. They could give any rating to player, just as they pleased and irrespective of how they already rated other players. Importantly, the players differed in terms of their nationality, name and skin color. And we found … nothing. Respondents were equally likely to give a good rating to black players as to white players; European players were equally rated as South-American ones.

Discrimination Unveils when Actions have Consequences

In the next task, we had our respondents choose between two – equally skilled – players. And all of a sudden, skin color became the decisive aspect for picking one over the other. What had changed? We constrained resources. While in the first game, respondents had no incentive not to be “generous”, the second game came down to a tough call for only one place in the team. They had to make a decision.

850 respondents were asked to rate the quality of or chose one of two football players

Such experiments may sound funny, but the translation into the real world is obvious: the vast majority in this country will tell you they have no issues with people of color, homosexuality, foreigners, etc. Partly, because they know society dislikes racists, but mainly – in my opinion – because people can say many things. The “truth” emerges only when we face consequences based on our statements or actions; when we have to decide where to spend our vacations; when we have to decide to whom we sit next to in the bus; when we have to decide whom we hire.

Pinning the Blame on the Society – an Easy Job

In the beginning, I wrote that we are all perpetrators of discrimination. It’s fascinating how something that shouldn’t exist in enlightened societies can still shape economic thinking, for instance. One justification that we often heard during our research is: “I am not a racist, but my clients may be!” This means, that people, such as employers, shift the blame to the society. Many studies have found that customer contact, for instance, is a reason for not hiring foreign employees, because employers worry that, say, a hotel guest feels uncomfortable to be served by a black receptionist.

Another example concerns unemployment. Caseworkers at job centers organize – besides standard counselling – training programs that should help unemployed persons finding a new job quickly. Strikingly, these caseworkers are more likely to assign the most beneficial programs – that is, those courses that really help you find a new job – to natives because they anticipate prejudice of employers, who, in turn, anticipate prejudice of customers. Put simply, if you are looking for a job and have a foreign background, a non-white skin color or the “wrong” religion, it’s likely that you won’t get the best training to find you a new job. This isnot because caseworkers at job centers are racist (maybe, probably not), but because investing into a non-native jobseeker is considered a waste of resources, as she or he will not find a job anyway in our society.

I don’t think I have to explain why this is a vicious circle for potential victims of discrimination. But ineffective hiring and job-search assistance are also detrimental to the rest of the society, because it creates situations where not the best qualified person for a job is hired, but the one who luckily has the “right” skin color or prays to the “right” god; things that are completely unrelated to any notion of qualification.

Swissmill, the world’s highest granary. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Which brings me back to the football players: let’s face it, we live with latent racism. Nothing else explains the fact that people make fully rational assessments – that is, independent of race or nationality – when asked about the skills of a football player, his “merit”. The “prejudice” kicks in, once actions entail consequences: when asked to make a decision between two, people almost exclusively picked the white player. Of course, we can speak out against discrimination. We can say many things as long as we don’t have to face real consequences. But when was the last time you invited the asylum seeker from next door over for dinner? And. have you really never thought “drugs” when you saw a black guy in the park at night? We are okay with building 120 meters of concrete to store flour in down-town Zurich, but the majority of us is not okay with a 20-meter minaret.

Latent racism, xenophobia, or misogyny allow employers, caseworkers, and random people to justify discriminatory behavior. In that sense, discriminating is even rational when the perpetrators have no resentments themselves: “I am not a racist, but my clients are!” Our everyday actions make it too easy to put the blame on the society. That’s why we are all perpetrators and prejudice prevails over merit.

Daniel Auer is a postdoctoral researcher at the Migration and Diversity department at the Berlin Social Science Center and a former doctoral student of the nccr – on the move.

– Auer, D., Bonoli, G., Fossati, F. and Liechti, F. (2019). The Matching Hierarchies Model: Evidence from a Survey Experiment on Employers’ Hiring Intent Regarding Immigrant Applicants. International Migration Review, 53(1): 90–121.

– Auer, D. and Fossati, F. (forthcoming). Compensation or Competition: Immigrants’ Access Bias to Active Labour Market Measures.

– Auer, D. and Ruedin, D. (2019). Who Feels Disadvantaged? Reporting Discrimination in Surveys. In: Steiner I and P Wanner (eds.): Migrants and Expats: The Swiss Migration and Mobility Nexus. Cham: Springer: 221-242.

– Auer, D., Ruedin, D. and Tichelbäcker, T. (forthcoming). Using Football Players to Capture the Dynamics of Discrimination.