How Can Previous Public Health Emergencies Help Us Understand the COVID-19 Travel Restrictions?

Even before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, research on restrictions to mobility in the context of public health emergencies had already highlighted a few key insights. We know, for example, that travel restrictions are driven by epidemiological, diplomatic and economic considerations; they cause major disruptions; and different communities use similar restrictions, which sometimes outlasted the emergency they were meant to contain. It seems therefore important to question how this knowledge could be used with new data sources to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the governance of mobility, migration, and citizenship.

Every government in the world introduced restrictions to human mobility – that is, the movement of persons across and within state borders – in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. While such restrictions constituted a global phenomenon, they were by no means globally uniform. Rather, they varied significantly between and within states, as well as over time. In a research note published in the International Migration Review, we argue that the global scale and variation of COVID-19 mobility restrictions may open new avenues for social scientific inquiry. Early studies of the restrictions focused on their epidemiological effects and their impact on patterns of human movement. By contrast, our findings suggest that the global variation in the restrictions as such and its implications for the ‘global mobility regimes’ – the legal and policy frameworks producing unequal opportunities to travel across and within state borders – are also significant in themselves.

What Can We Learn from Previous Public Health Emergencies?

Research on mobility restrictions introduced during previous public health emergencies generated five key insights.

- During pandemics, countries limit human movement not only in response to changing global epidemiology but also based on other criteria, including diplomatic and economic considerations.

- Different communities tend to use broadly similar measures to curtail human mobility during public health emergencies.

- Travel restrictions introduced during pandemics cause significant economic disruption to affected communities.

- Restrictions to mobility have often been accompanied by exceptions for specific groups of individuals based on their legal or professional statuses.

- Restrictions have sometimes outlasted the emergency they were meant to contain, creating new categories of desirable and undesirable travelers.

These earlier research findings convinced us to study the travel restrictions introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic further to further improve our understanding of mobility, migration, and citizenship governance. We, therefore, propose five research avenues to examine such restrictions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In each case, we provide an illustrative example of the kind of analysis that could be done.

Drivers of the Mobility Restrictions

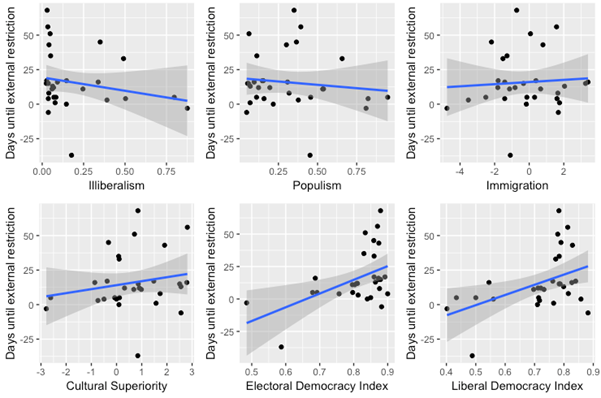

The global variation in mobility restrictions raises the question of why different governments made different policy choices in response to the pandemic. The drivers of these choices could include, for example, medical and epidemiological concerns (e.g., number of cases in the target countries), party ideology (e.g., liberal governments may be more reluctant to restrict mobility), transnational alliances (e.g., formal trade and mobility agreements between countries may limit the introduction of reciprocal travel bans), policy learning (e.g., experience with previous epidemics like SARS, MERS or Ebola), the structure of the government (e.g., federal countries may be slower in introducing restrictions), and economic policy (e.g., reliance on migrant workers may force states not to restrict labor-based mobility). Furthermore, domestic and international mobility rules are often driven by different sets of expectations and policy dynamics.

Figure 1. The timing of the first international mobility restriction introduced, correlated with party ideology and level of democracy (EU and EFTA countries)

Source: Own elaboration based on Cheng et al. 2020; Coppedge et al. 2021; Lührmann et al. 2020; Piccoli et al. 2020b.

Source: Own elaboration based on Cheng et al. 2020; Coppedge et al. 2021; Lührmann et al. 2020; Piccoli et al. 2020b.

Patterns of Policy Convergence and Divergence

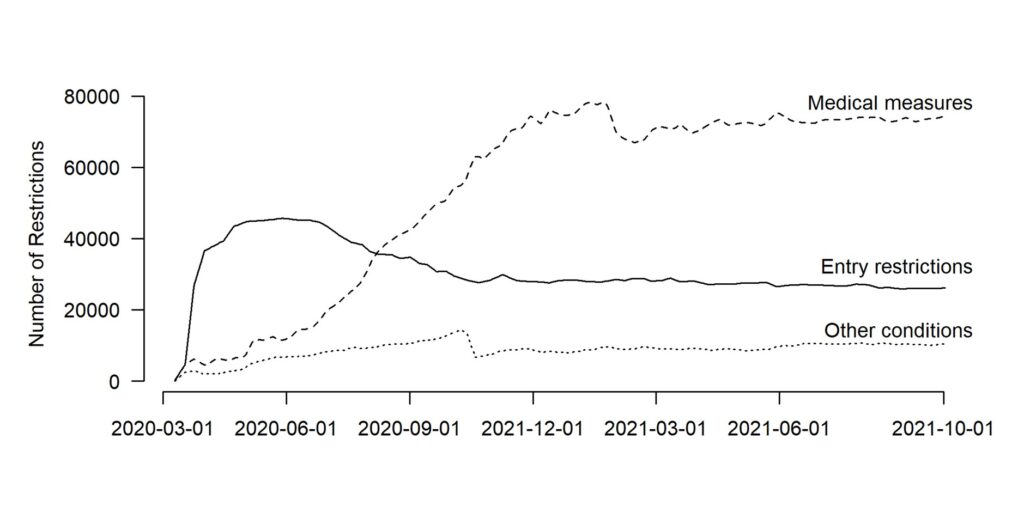

Comparative political scientists may find patterns of policy convergence and divergence by exploring international policy diffusion over time. For example, in June 2020, most states restricted entry, but only a few deployed public health measures (such as a test or screening) as conditions for border crossing. By June 2021, the number of travel bans decreased, while the number of public health measures regulating entry significantly increased.

Figure 2. Evolution of international travel restrictions by type between March 2020 – October 2021

Source: Own elaboration based on IOM (2021).

Source: Own elaboration based on IOM (2021).

The Legality of Mobility Restrictions

The scope and duration of COVID-19 mobility restrictions raise questions about their compatibility with pre-existing legal norms permitting human movement. Article 12(4) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, for example, states that “no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of the right to enter [their] own country.” However, some countries including Australia and Morocco prevented their own citizens from entering their territory, and thus potentially acting in breach of their international human rights obligations. The legal scholarship could also assess whether implementing internal mobility restrictions is constitutional – that is, how compatible would such an act be with domestic constitutional norms limiting the reach of government powers and protecting fundamental rights, such as freedoms of association and assembly.

Continuity and Change in Global Migration Policy

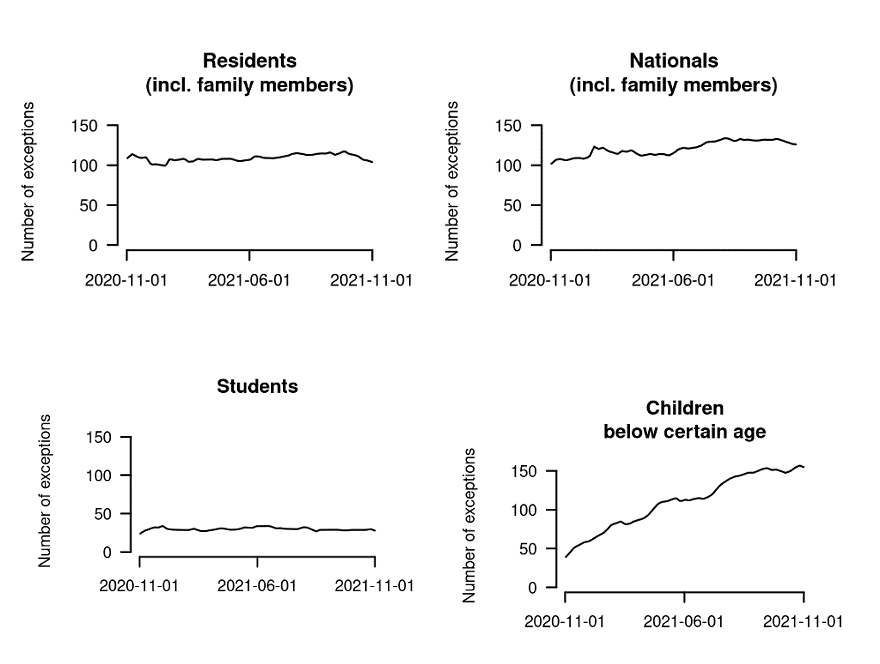

COVID-19 mobility restrictions did not target all individuals uniformly, but their effect was felt rather differently depending on the individuals’ countries of origin and legal statuses (citizen, temporary resident, asylum seeker, and so on). In this way, the restrictions exemplified a broader trend in contemporary migration policies, which operate as a selection mechanism based on similar characteristics. For example, an assessment of which migrant workers were exempt from international border closures – such as medical staff, transport personnel, or agricultural workers – could explore trends in the understanding of ‘essential’ labor migration during the pandemic.

Figure 3. Evolution of the exceptions to international travel restrictions between November 2020 – November 2021

Source: Own elaboration based on IOM (2021).

Source: Own elaboration based on IOM (2021).

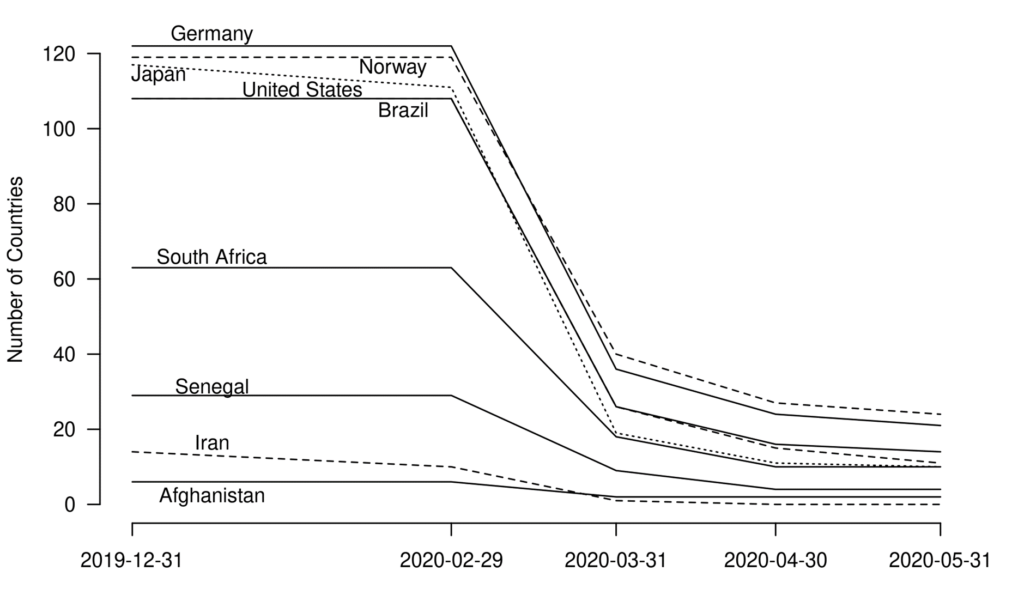

Citizenship and International Mobility Rights

Since before the pandemic, the right to cross state borders has been closely tied to a person’s citizenship, with much greater international mobility rights traditionally awarded to citizens of states in the Global North. COVID-19 mobility restrictions raise questions regarding the continued importance of citizenship for international mobility rights during the pandemic, for instance, whether citizens were still permitted to return to their countries of origin, and whether the citizenship of Global North states continued to guarantee more far-reaching international mobility rights.

Figure 4. The relative decline in the number of countries that selected passport-holders could access without a visa

Source: Own elaboration based on Recchi et al. 2020 and Piccoli et al. 2020a.

Source: Own elaboration based on Recchi et al. 2020 and Piccoli et al. 2020a.

What Can We Learn from This Research?

Taken together, these five research avenues can advance our understanding of the effects of a public health emergency on global mobility regimes. We therefore strongly encourage scholars to study the mobility restrictions introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic further and explain their drivers, their evolution over time, their legality, their relationship with pre-existing mobility controls, as well as the uneven effects they had on different groups of travelers. This public health emergency offers an unprecedented opportunity to examine such mobility restrictions, given both the global scope and variation of the restrictions imposed and the wealth of available data capturing them.

Jelena Dzankic is Part-Time Professor at GLOBALCIT, European University Institute.

Timothy Jacob-Owens is Early Career Fellow at the Edinburgh Law School, University of Edinburgh. Lorenzo Piccoli is Research Fellow at the Migration Policy Centre, European University Institute.

Didier Ruedin is Senior Lecturer at the University of Neuchatel and a Project Leader at the nccr – on the move.

Acknowledgment: this research is a collaboration between GLOBALCIT, the Migration Policy Centre, and the nccr – on the move and is concurrently being posted on these platforms.