What Happens When a Transnational Researcher Cannot Travel Anymore?

The pandemic impacted people’s transnational movements as well as research on mobility and migration. As a Ph.D. student doing multi-sited research, I used to cross national borders several times a year to do fieldwork, but suddenly I was forced to immobilize. What happened next, to me as a researcher, to my research and its participants?

My research focuses on Portuguese labor migrant couples, mobility and relocation after retirement. As I engaged in multi-sited ethnography, I used to travel every two to three months between Lisbon, where I live, and Switzerland, where most of my informants reside. They used to be frequent movers themselves: low-cost airline tickets have facilitated regular back-and-forth movements, especially for retirees who can travel outside the high season and on weekdays. They used to go to the South for a few days or weeks, several times a year, to visit their family, to look after their holiday home, for harvests, to have access to cheaper dental care, to participate in local festivities, etc. Moreover, retirees who had relocated to Portugal used to come to the North to support their children or participate in family celebrations, among other reasons.

I was interested in critical elements that influenced aging migrants’ mobility. But one day everybody stopped moving because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Yet, this did not mean stopping transnational research.

What Has Happened to the Researcher, the Research and its Participants Since Last March?

Mid-March 2020, when the first lockdown was declared in Portugal, nurseries, schools and universities closed, remote working became the norm, and my flight to Geneva was canceled. I decided to start a coronavirus diary — like many people, I suppose. Online research on media, airports’ websites and migrant groups’ Facebook pages became part of my daily routine.

By the end of March, almost all flights between Switzerland and Portugal were canceled. Easyjet and TAP put their entire fleet onshore, with no date set for resuming air traffic. Only SWISS maintained a small number of connections between the two countries. Due to this scarcity of flights, both my interlocutors and I could no longer move freely, and nobody knew when this would be possible again.

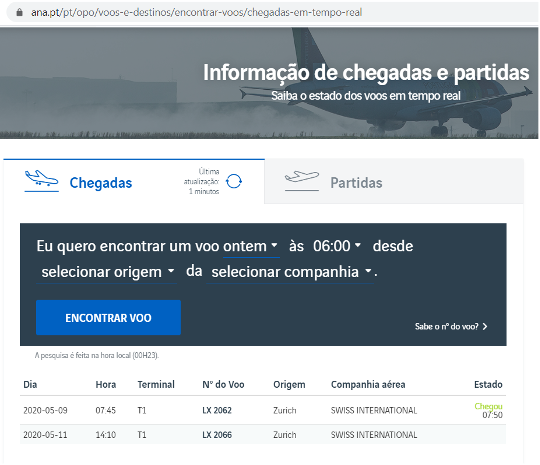

11th May 2020: Information about arrivals at the Oporto Airport website. Incoming and outgoing flights were scarce and, for some days, SWISS airplanes from Zürich were the only flights announced on the Arrivals panel.

I did not want to lose contact with the field in the meantime. I started texting and calling my informants to find out how they were doing. Some people felt trapped, such as Nanda’s husband, who had recently retired in Switzerland and had gone to Portugal to visit his family. He was now afraid to get infected on his way back. Or Maria, who was visiting her children in Switzerland for the first time after returning to Portugal. She was worried that her flight home would be canceled, as she wanted to return to her husband. Others felt deprived of their freedom, especially men, who are less used to being in the ‘inner space’ of one’s home than women (due to gender roles!). “Now they say we can’t go out,” complained a man who had moved back to Portugal after living in Switzerland for 30 years. “I get bored. Sometimes I’m a little stressed. My wife is calmer. She does the housework. She doesn’t complain. She feels good.”

Like most, my interviewees felt anxious about the uncertainty of these pandemic times. Most suspended or postponed their summer travel plans, first to September, then to October 2020, and finally to 2021… A few only stuck to their plans and were lucky to travel without any setbacks.

In any case, I have observed that older Portuguese migrants have reduced their movements considerably since the beginning of the pandemic. First, they were afraid of being infected when traveling. Then, the new restrictions came into force, such as the quarantines imposed by the Swiss government on travelers coming from Portugal in October and December last year.

In 2020, returned retirees were less mobile than Portuguese retirees in Switzerland, and so were their (grand-) children abroad. To protect the elderly, geographically dispersed families chose to stay apart and not to celebrate birthdays or Christmas together. Instead, virtual communication such as video calls, which were already a common practice to create co-presence in transnational families, became a daily routine for many interviewees. The uncertainty about when would they be able to see and kiss each other again was overcome by the hope in science (vaccine), or in religion. “May God help us! We must have faith, it is what saves us,” one of my interviewees told me the last time I called her.

In the beginning, we thought we were all in the same boat, and then we realized the pandemic has exposed existing inequalities. In my research, for example, I could observe retirees, who had returned to Portugal, were in a more privileged situation since most of them live in peripheral or rural areas, in spacious houses with gardens and sometimes animals. However, because migrants’ social position differs from one country to another, those who had remained in Switzerland generally live in modest urban flats, and a few lucky ones grow an urban vegetable garden.

The Limits of Online Research

Messenger and WhatsApp have been solid allies to keep contact with informants. I was able to gather additional information from people I had previously met in person, but this was usually restricted to quite short, factual sentences. The nonverbal and other information I used to collect through direct observation, however, are missing. Without the face-to-face contact of fieldwork, the data collected lose their ‘thickness.’ What is more, I was no longer able to meet occasional informants spontaneously in public spaces. I cannot take pictures anymore or make drawings of the contexts in which interlocutors live, no more chitchat with unknown people traveling in the same plane

2021 Finally Came… And Now What?

I had finished a previous draft of this text with a positive note: “Hopefully, 2021 will give us back face-to-face contact.” However, while revising the final draft, multiple variants of the virus are circulating globally and the situation in Portugal has deteriorated. We are facing a second, stricter lockdown and national citizens are not allowed to travel abroad, while a negative PCR test is required for people coming from other countries. Following the latest developments, both participants in my research and their offspring continue to postpone their visits to each other and loss is becoming one of the predominant feelings. “I don’t see my parents [since December 2019] and it’s hard for me to lose a year of their life,” texted me a 40-year-old Portuguese-Swiss woman, whose parents returned to Portugal some years ago.

Indeed, for transnational family members – like myself as an ethnographic researcher – the pandemic has led to the loss of the three-dimensionality of life, and it is more and more difficult to cope with the perspective of a lack of freedom of movement in the times to come.

Liliana Azevedo is a Ph.D. student at Iscte – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa and an associated doctoral student to the nccr – on the move who collaborates with the project Transnational Ageing: Post-Retirement Mobilities, Transnational Lifestyles and Care Configurations. Her work is supported by the Portuguese national agency for scientific research (FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia), which granted her a doctoral scholarship (Reference SFRH/BD/128722/2017) for which she is grateful for the financial support.