A Pacific Perspective on Climate-Related Migration

Pacific Island countries have globally been at the forefront of research, media, and policy discussions on climate mobility. These island nations have been predominantly categorized as « climate migrant-sending countries » – particularly so in Europe, where media and Western scholarship have painted an overly simplistic picture in which « all Pacific Islands are doomed to sink. » Based on my recent publication, this blog offers a Pacific perspective and argues that climate-related mobility research and policy need to pay more attention to migration between Pacific Island countries.

Climate change plays an additional and increasingly important role in shaping human mobility (including migration, displacement, and planned relocation) in the Pacific Islands region. The island nations face significant challenges from more frequent and severe climate-related stressors, such as cyclones, flooding, sea-level rise, and other climate-related impacts, resulting in substantial loss and damage to Pacific Islanders’ lives and livelihoods.

Due to this high exposure and vulnerability to climate change, Pacific Island countries (PICs) are often framed as « climate migrant-sending countries. » This dominant framing is problematic in two ways: First, determining how populations react to different types of climate-related risks and untangling these effects from other multiple determinants of migration is challenging, which emphasizes the complexity of climate-related migration. Second, depicting all PICs as « sending countries » conceals a focus on migration between Pacific Island countries.

Dominant Depictions – and the Blind Spot

So far, studies on climate mobility have unanimously portrayed Pacific Island countries as « migrant-sending » countries. Some have even claimed that “Pacific islands do not have a history of receiving international migrants.” A similar perspective is prevalent in international organizations and donor agencies, which categorize PICs as migration “outlets” and non-Pacific Island countries as receiving regions.

Contrary to these dominant depictions, my article provides evidence that population movements and « migrant-receiving » countries within the Pacific Islands region are a reality but this has so far remained a blind spot in climate mobility research and policy:

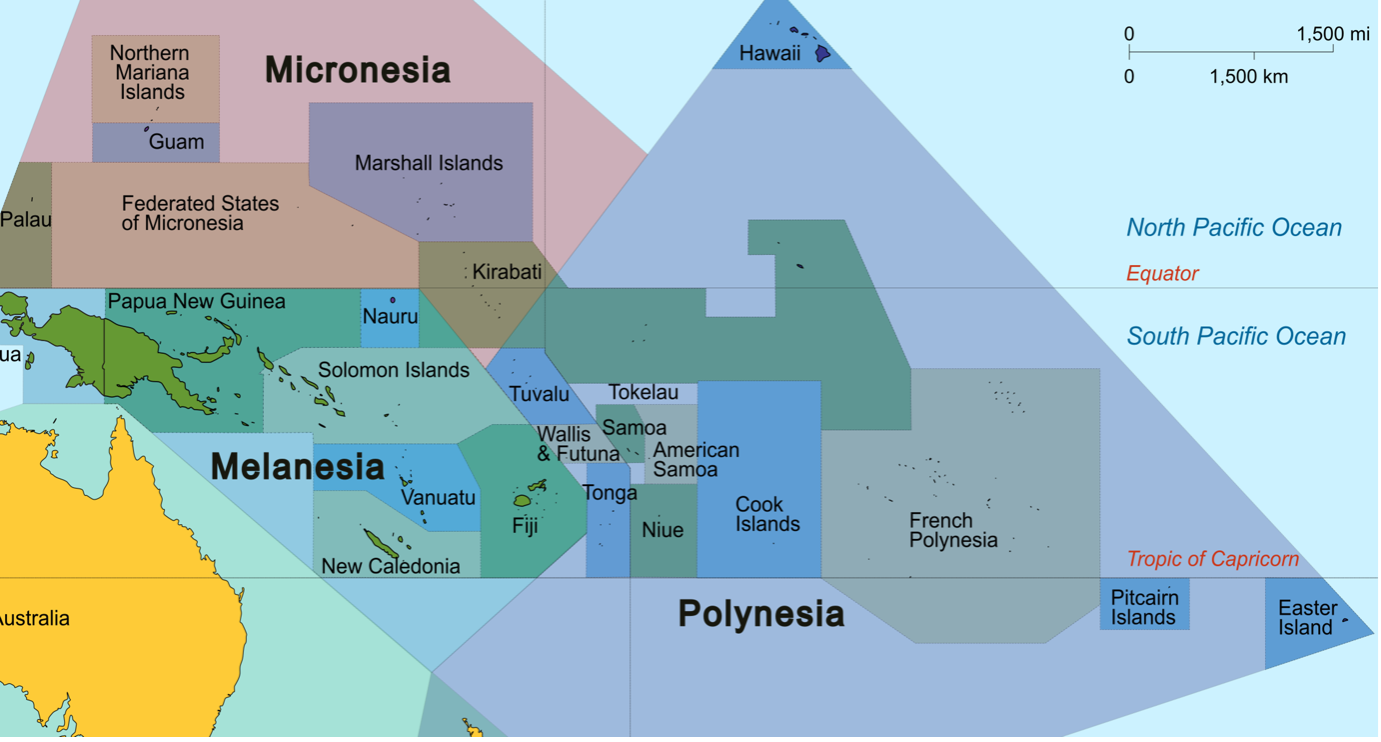

- Research has predominantly looked at migration out of the PICs region to the Global North (particularly the Pacific Rim countries, such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States), neglecting population movements within the Pacific Islands region where there are 22 countries and territories (see Figure 1).

- Similarly, key past and current foreign aid-funded climate mobility projects in the Pacific region have mainly focused on climate- and disaster-related (i) migration from PICs to high-income foreign countries, (ii) internal planned relocations within national borders, and (iii) internal displacements within national borders. Inter-Pacific Islands migration (IPIM) has not been given much attention in donor-funded climate mobility projects.

Figure 1: Map of the Pacific Islands Region

Source: Wikimedia Commons

It follows that migrant-receiving countries within the Pacific Islands region, such as Fiji, have so far been insufficiently considered in academic research, national and regional policies, foreign aid, and media reporting.

Fiji: An Example of a Migrant-Receiving Country

My research findings highlight that Fiji, like other Pacific Island countries, is widely regarded as a migrant-sending country. However, migration and planned relocation of communities across international borders to Fiji are significant.

International migrant numbers in Fiji have been on an increasing trend since 2010. As of 2020, there were 14,087 international migrants in Fiji, representing approximately 1.8% of the country’s total population. Compared to other PICs (excluding Papua New Guinea), Fiji had the highest number of international migrants present in 2020.

Historically, substantial population movement to Fiji from other Pacific Island countries has been occurring since pre-colonial times and has continued during the colonial and post-colonial eras. Fiji has long been a destination for intra-regional resettlement in the Pacific. At various points in Fiji’s history people from Kiribati, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu came for trade, as environmentally displaced people, or as forced laborers. Currently, immigrants from PICs account for almost a third (27%) of the total immigration numbers to Fiji.

My field research among local communities in urban and rural areas in Fiji shows that immigration to Fiji from other Pacific Island countries is affecting the lives of local Fijians. Local Fijians are concerned about the absence of appropriate national policies to address climate-related immigration. They fear that cross-border climate-related immigration from other PICs could have negative effects on their own livelihoods.

Why is Inter-Pacific Islands Migration (IPIM) Important?

Not considering inter-Pacific Islands migration in climate-related mobility research and policy means ignoring a significant part of the migration pattern in the Pacific region: It embodies a Western-driven research agenda based on the interests of foreign countries, forecloses policy options in the context of climate-related migration, and nourishes Eurocentric media narratives.

As I argue in my article, there is a pressing need to rethink research agendas and policies on climate-related migration in the Pacific by recognizing IPIM to a greater extent:

- More research on inter-Pacific Islands migration is needed to fill knowledge gaps. Significantly more aid-funded support is required for data collection and data management specifically tailored to climate-related migration between Pacific Island countries. In doing so, investing in disaggregated data is fundamental to shed light on the demographics of those who migrate, the extent to which climate change determines immigration to Fiji and migration among other PICs, and the extent of such movements.

- It is crucial to prioritize the voices of local communities and to harmonize policymaking with the social realities and everyday lived experiences of those affected. As the prevalent narrative of Pacific Island countries has often focused on them as mere origins of migrants, migrant-receiving communities within PICs (such as those in Fiji) have been neglected in research and policy. Recognizing and extending assistance to the migrant-receiving communities in PICs – akin to support programs for migrants – is crucial for supporting local populations in areas where migrants are present.

Ultimately, the ignorance of inter-Pacific Islands migration leads to incomplete research and policy on (climate-related) migration in the region. A greater emphasis on IPIM is pivotal for comprehensively understanding the dynamics of climate-related migration between PICs and for effectively addressing climate-related migration in the Pacific Islands region.

Sargam Goundar is a Doctoral Researcher in Geography at the University of Otago and a former nccr – on the move Visiting Fellow under the project “Crisis Influence on Discourses and Policies of Migration.” Her expertise lies in climate- and disaster-related mobility research and policy in Oceania and beyond.

Publication:

-Goundar, S. (2023). Should foreign aid consider inter-Pacific Islands migration in the context of climate change? Evidence from Fiji. Development Policy Review, 41(Suppl. 2), e12742.

Further Reading:

-Goundar, S. (2022). Local perceptions of Fiji as a receiving country in the context of climate change-related migration. The Aotearoa New Zealand International Development Studies Policy Brief (DevNet).

References:

-Asian Development Bank. (2011). Climate change and migration in Asia and the Pacific.

-Kelman, I. (2014). No change from climate change: vulnerability and small island developing states. The Geographical Journal, 180(2), 120–129.

-United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2020). International migrant stock 2020.

-Wyett, K. (2014). Escaping a rising tide: Sea level rise and migration in Kiribati. Asia and the Pacific Policy Studies, 1(1), 171–185.