National Identity through Images in UDC’s Campaign Posters

“Enough is enough” and “We are too tight!”- are two of the slogans illustrating the type of political discourse that has emerged out of the current political campaign to limit migration in Switzerland. This call to limit migration is not a new phenomenon, it is just a repetition of the 20th-century politicization of the “foreigner.” Such political narrative has always been contentious, given the fact that the discourse expressed via these images is centered around the concept of who belongs and who does not, and because it is based on an imagined idea of a community with exclusive ideals or norms.

A Nation Imagined

The term imagined communities is rooted in anthropology and political science and studied within the context of phenomena related to nationalism and national identity. According to Benedict Anderson, the nation is a socially constructed community, imagined by the people who perceive themselves as part of that group (Anderson 2016). Members of a community thus hold a certain mental image of their affinity to a group. Such mental images can consist of norms, behaviors, and physical or geographical boundaries (Anderson 2016), which consequently produce an exclusive set of criteria of who does and does not belong to a community. In the case of the two posters produced by the Democratic Union of the Centre (UDC), these criteria may be seen through text and illustrations.

Multimodal Discourse Analysis: Understanding Discourse Through Images

Discourse has a crucial role in the political process and political posters can be powerful media to communicate a persuasive message to an audience (Benderbal 2017; Jones 2012; Kress & Leeuwen 2010; Popova 2012). Traditionally, discourse is analyzed by looking at the text. However, discourse can also be analyzed via images using multimodal discourse analysis, which focuses on the study of language in conjunction with other modalities such as images, music and graphs (Benderbal 2017; Fairclough & Fairclough 2012; Jones 2012; Kaid 2012; Kress & Leeuwen 2010; Martínez Lirola 2016).

A political poster is, therefore, a clear example of multimodal discourse because it combines more than one mode of communication, namely text and images. When looking at multimodal discourse, one needs to examine it as a whole, a combination of the different modes that create meaning in an effective way (Benderbal 2017; Fairclough & Fairclough 2012; Jones 2012; Kaid 2012; Kress & Leeuwen 2010). To proceed, one must examine the multimodal text from the perspective of the choice of font, place in which the image appears on the page, use of vocabulary and syntactic structures, etc. (Kress & Leeuwen 2010).

So, What Do the Posters Mean?

Both posters from UDC’s campaign provide rich multimodal material to study how their designers use visual and discursive tools. In the first poster, we see an image of a large bottom of a person wearing a blue belt with golden stars, squishing and cracking what can be seen as a map of Switzerland, with a text stating, “Enough is enough” in bold black letters.

Based on the visual elements, one can infer that the person in question is a representation of the European Union or a person from the EU, given the colors of the belt or the plumber’s crack, and their position of sitting on a map of Switzerland, indicted by its colors and borders, causing it to crack. These images, colors, symbolic images and the placement of the text evoke a clear message; the European Union or citizens of the European Union are crushing Switzerland, which is cracking under their weight. Not only is the message direct, but it also is a good visual example of how the concept of imagined communities is applied in representing a nation and who may be seen as included or excluded – in this case, EU nationals.

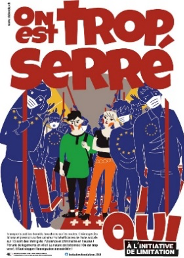

The second poster seems to have a similar message. Unlike the previous poster, the header is at the top stating, “We are too tight” with an image below it. The image depicts two people using the tram, who are surrounded by other people wearing masks. Once again, the color and positioning of an object are being used to differentiate between the Swiss and EU nationals. The Swiss, pictured as multi-colored, are standing in the middle of the tram on top of images of the Swiss flag versus those from the EU, who are pictured in blue with yellow stars standing on the sides of the tram – outside of the flag. Through all these visual elements, a simple message may be inferred: EU nationals are causing the tram to be overcrowded during a pandemic and are therefore engulfing the Swiss.

If this image was unclear in delivering a political message, the tiny text below in the left corner says it all: “Crowded public transport, traffic jams on the roads. Unemployment in the 50s and pressure on wages! 6 out of 10 welfare recipients are immigrants! Violence and criminality on the rise! Housing shortage in the city! Nature is concrete! We are too close together! We must stop uncontrolled immigration.” In both the images and the text, the narrative is clear: EU nationals are to blame for a myriad of social problems, which threatens the Swiss way of life.

Just as the previous poster, this poster provides both a visual and textual example of how Anderson’s theory of imagined communities can be applied in conceptualizing the nation. This poster, in particular, visually encapsulates the ongoing debate on the politics of belonging and provides a demarcation line between who is Swiss and who is foreign. This demarcation line can be found in an interpretation of the multimodal discourse, which evokes a specific list of norms and behaviors that are not accepted. According to this interpretation, to be included in the Swiss community one cannot be a “burden to the state” in any form, whether it be socially or financially. This seems to be how members of the UDC political party imagine their community and what it means for them to be Swiss.

Leslie Ader is a doctoral student and researcher in migration and mobility at the University of Neuchâtel associated to the nccr – on the move in the project on Historical Perspective on Mobility in Welfare States and focuses on History of Welfare States, Discourse, Claims-Making, and Welfare Policies.

References:

– Anderson, B. R. O. (2016). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Revised edition). Verso.

– Benderbal, A. el H. (2017). A Multimodal Discourse Analysis of Local Election Posters in Algeria [Master’s Degree in language sciences, University of Mostaganem].

– Fairclough, N. & Fairclough, I. (2012). Political Discourse Analysis. Routledge.

– Jones, R. H. (2012). Multimodal Discourse Analysis. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. American Cancer Society.

– Kaid, L. L. (2012). Political Advertising as Political Marketing: A Retro-Forward Perspective. Journal of Political Marketing 11(1–2), 29–53.

– Kress, G. R. & Leeuwen, T. van (2010). Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design (2. ed. reprinted). Routledge.

– Martínez Lirola, M. (2016). Multimodal analysis of a sample of political posters in Ireland during and after the Celtic Tiger. Revista Signos 49(91), 245–267.

– Popova, M. (2012, June 4). A Visual History of Presidential Campaign Posters: 200 Years of Election Art from the Library of Congress Archives. Brain Pickings.