The Biopolitics of Fan Filtering : Qatar’s Post-Pandemic Mobility Regime

During the FIFA 2022 World Cup, Qatar devised several ad hoc migration policies to dramatically curb the total number of visitors in favor of a preferred type of soccer fan: well-off and depoliticized. Profiting from a global state of exception during the COVID-19 pandemic, Doha further refined its mobility regime during the games, a move that went largely unnoticed in global media coverage.

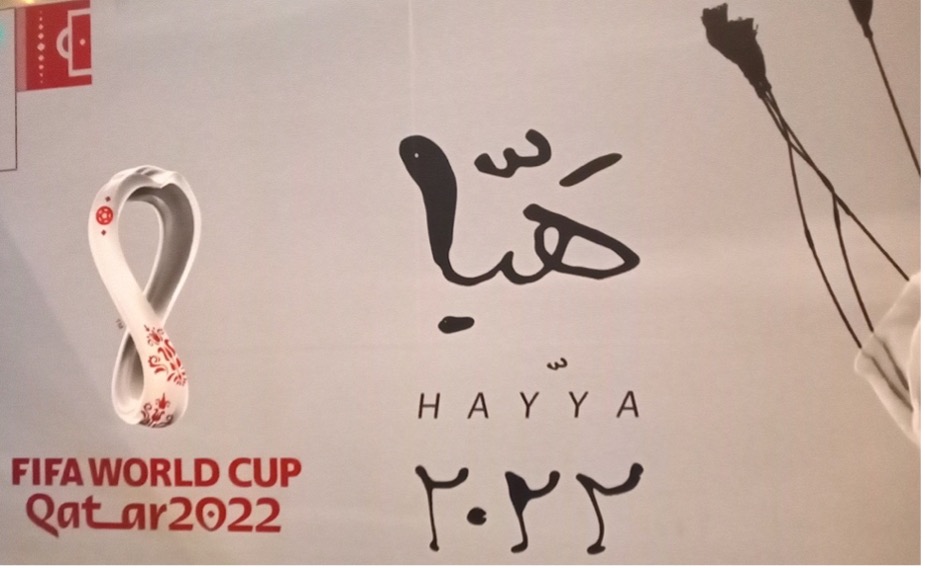

On April 4, 2022, the online ticket sales began for the FIFA World Cup in Qatar. That same day, Qatari media outlets quietly reported a sudden change in Qatari immigration policy: Entry during the World Cup would be permitted only through the purchase of (limited and pricey) FIFA match tickets. Qatar had already instituted a special e-visa scheme for the tournament, the so-called “Hayya Card,” forcing everyone planning to travel to Qatar to apply prior for an online “fan ID” to pre-vet personal data. Working-class fans hoping to support their teams outside of the stadium premises, and join local festivities, were now barred from traveling to Qatar.

Source: A bilingual Hayya Card advert displayed in Qatar, November 2022. Photo: Jaafar Alloul.

Source: A bilingual Hayya Card advert displayed in Qatar, November 2022. Photo: Jaafar Alloul.

This classist policy of fan filtering was largely ignored but is indicative of a profound normalization of sudden mobility curbs in the wake of the pandemic. In addition to restricting travel, Qatar charted new terrains of statecraft and oversight, not least by launching a mandatory tracking app on mobile phones for all citizens and residents, called „Ehteraz,“ with non-compliance punishable by fines up to “$55,000 or three years in prison.” During the pandemic, Qatar’s ambiguous mobility legislation also disproportionately affected working-class strata, leaving some unpaid (foreign) workers “stranded” inside the country yet unable to pay housing fees. The subtle exclusion of certain fans right before the World Cup, and the stranding of others during the tournament itself, thus hold eerie resemblance to the COVID-19 mobility regime.

The Biopolitics of Fan Filtering

Qatar cited capacity limitations and general safety concerns for incoming fans as reasons for its sudden immigration restrictions. With only 300,000 Qatari citizens, and overall ticket sales exceeding 2.4 million, Qatar was aiming big indeed. Being one of the richest countries in terms of GDP per capita, however, and given that Doha had over a decade to prepare for the World Cup, suddenly barring all ticketless fans seemed extraordinary, even for such a small state. Equally peculiar was that while Qatar was scrutinized intensely in Western media for its human rights record, stance on LGBTQ+ attendees, and labor exploitation of migrant workers – leading to a Boycott Qatar 2022 movement in Europe – no one picked up on how a large number of global soccer fans, especially those on tight work schedules, had to cancel their plans due to a purposely confusing border regime.

The briskness with which Qatar announced its policy changes suggests that state authorities were anxious about the World Cup’s potential to challenge the established social contract in Qatar, which economically favors and socially insulates a demographic minority, the Qatari citizenry. At 12 percent of the total resident population, Qataris make up an elite stratum in the country. The great majority of residents are low-wage workers from the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, whose presence is tightly regulated by the country’s infamous kafala sponsorship system. Given that the World Cup is one of the most-watched sporting events, the stakes were high in the event of upheaval. The Hayya Card regulations thus reveal three key policy variables at play: to curb the total number of visitors, keep out as many working-class visitors as possible, and exclude overtly politicized soccer fans. Two examples demonstrate these biopolitical rationales.

Prior to Qatar’s last-minute visa restriction disallowing ticketless fans entry, alcohol was suddenly banned at stadiums and most of the FIFA fan zones in Doha. Compounded with the high cost of hotel stays in Doha and the administrative hassle for Western travelers otherwise used to privileged visas, ensured that working-class European fanbases were noticeably absent in November 2022. Many England and Wales fans were seen swapping Qatar for more affordable (and liberal) leisure destinations like Tenerife in Spain. Tenerife was then scene to massive street and pub brawls, after which the Tenerife authorities issued a public statement saying that they too – much like Qatar – would like to attract a “better class of tourists” in the future. This demonstrates how post-COVID policies, especially in the form of restrictive, if not highly classed, mobility regimes continue to travel in the bureaucratic imagination of lawmakers the globe over.

Confusion became even greater when Qatar suddenly announced that following the group phase of the tournament, ticketless fans would be allowed in after all. In a surprise move, and once the knockout phase was well underway, Doha then suddenly reversed its decision, at least for ticketless fans from North Africa. Despite many ordinary Qataris praising their fellow Moroccan ”Arabs” for unexpectedly making it to the semi-finals, the authorities sought to counter the entry of politicized (anti-monarchical) Moroccan soccer fans.

Source: Saudi fans arriving in a FIFA World Cup “fan village,” November 2022. Photo credit: Jaafar Alloul.

Source: Saudi fans arriving in a FIFA World Cup “fan village,” November 2022. Photo credit: Jaafar Alloul.

The Moroccan national team went on to become the first-ever Arab and African country to conclude the tournament in a historic fourth place. In the hope of joining the festivities, the number of Moroccan fans booking flights from Morocco to Qatar rose exponentially, and Royal Air Maroc agreed to charter additional flights. Yet, while the Qatari authorities were publicly basking in Morocco’s achievements, state-owned Qatar Airways suddenly pulled out of the joint deal with Royal Air Maroc, leaving the latter baffled and many Moroccan fans stranded.

Much like curbing working-class fans from Europe during the opening phase of the tournament, Qatar’s entry restrictions and legal ambiguity during the knockout phase clearly targeted young working-class males from North Africa. Moreover, with no restrictions reported in relation to the European-Moroccan diaspora traveling to Qatar, these classist policies may also reveal intra-racial hierarchies of Gulf disdain for the more “underdeveloped” Western (Maghreb) regions of the Arab World.

Population Management as State Building

With their team eliminated early on, Qatari spectators as well as the Qatari Emir seemingly embraced the success of other regional teams, such as Saudi Arabia and Morocco. However, many Moroccan fans were deliberately kept out of the country. While appropriating FIFA’s first-ever “Arab” World Cup to stage a defiant script on “postcolonial” sovereignty in the face of Western human rights criticism, Qatar was simultaneously fortifying its state apparatus and filtering out “peripheral Arabs” it deemed a potential political nuisance.

I observed Qatar’s arbitrary entry policies first-hand during Qatar’s World Cup edition, while having visited the country several times during the immediate aftermath of the pandemic. There was significant continuity in terms of its mobility and citizenship regimes over time; the pandemic, like elsewhere, was no temporal ”exception” after all. Building on its response to the pandemic, Qatar refined its (online) surveillance tools while crafting a specific FIFA entry regime that would pre-empt politicized forms of (anti-monarchical) popular unrest during the games.

For Doha, an ascending global powerhouse, the World Cup functioned as a bureaucratic test case in expanding the state’s capacities. The trend in Qatar is not exceptional, however, and serves as one of many examples of the biopolitical legacies of COVID-19.

Jaafar Alloul is an Assistant Professor of Cultural Anthropology at Utrecht University, specializing in migration sociology, political economy, and cultural transformation in the Gulf Arab states. He is also a Visiting Researcher at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service in Qatar.

This blog post is part of our series „Towards a Novel Mobility Regime.“