A New Pact on Migration and Asylum: What Changes for Responsibility-Sharing in the European Union?

After more than three years of negotiations and just before the upcoming elections of the European Parliament, the European Union (EU) reached a provisional agreement on a new migration deal. Hailed as a historic agreement that will overhaul the EU’s migration and asylum policy framework, how would this deal change the system of responsibility-sharing, and will it establish the long-awaited solidarity between member states?

The new deal that was agreed in principle in December 2023 seeks to address a persistent problem: the Common European Asylum System is largely dysfunctional and refugee arrivals are highly asymmetric among member states, with them showing little appetite for more solidarity. In the current system, responsibility for an asylum request is assigned primarily to the country of first entry, mostly the frontline countries in Southern Europe. Numerous attempts to establish a fair(er) sharing of responsibilities failed either to reach a political agreement or to be effectively implemented due to non-compliance by member states and asylum-seekers. Despite a broad consensus on the need for reform, the EU has hitherto failed to find a political solution that would reconcile the asymmetric interests of member states and establish effective responsibility-sharing.

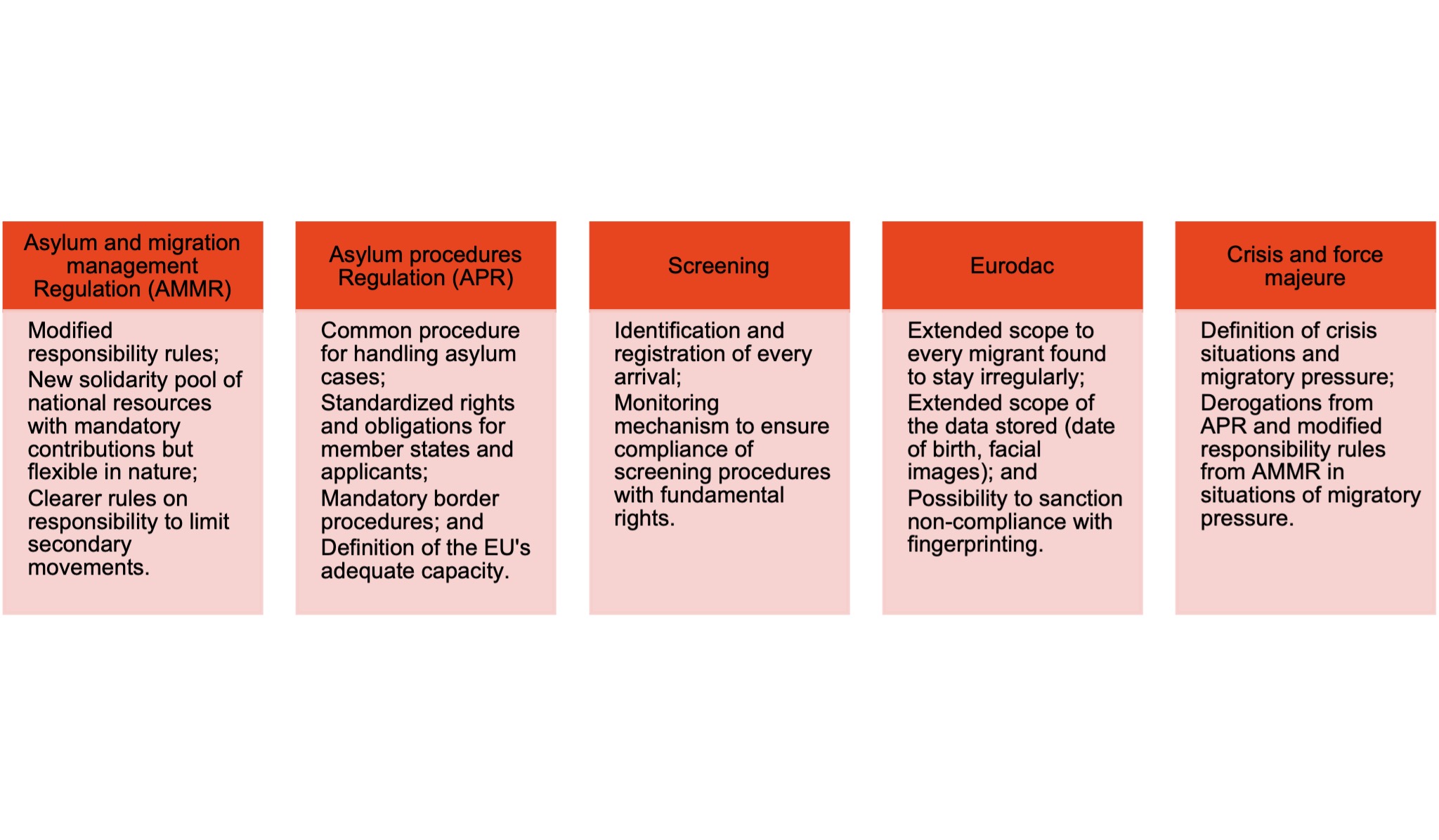

The New Pact on Migration and Asylum is the latest attempt to address this challenge. While the technical details are still under work, the formal approval is expected this spring as a strong signal to European voters that the EU is capable of effective political action on this crucial issue that is looming large in the upcoming elections of the European Parliament. The legislative package agreed upon in principle focuses on several key developments, namely the reinforcement of external borders, the modification of responsibility rules, the inclusion of mandatory solidarity provisions, and the harmonization of procedural arrangements to handle and process arrivals at the border and asylum applications (see overview in the figure below).

New Foundation or Just Another Layer?

New Foundation or Just Another Layer?

A large part of the New Pact is concerned with a better distribution of responsibilities among member states in enforcing EU migration policies. This involves a number of new measures and rules that seek to operationalize solidarity between member states and thereby contribute to fairer responsibility-sharing.

So far, the Commission insisted that a common European asylum policy should involve mandatory relocation quotas, an idea that caused significant political backlash and resulted in infringements by several member states. In contrast, the New Pact abandons such a fixed obligation by allowing for additional ways in which member states can share responsibility, namely the sharing of resources through financial and capacity-building contributions. At the same time, the EU seeks to strengthen the sharing of norms, i.e., efforts to harmonize migration and asylum policies to disincentivize secondary movements and “asylum-shopping.” This takes place by turning the Directives into more binding Regulations and the standardization of procedures throughout the EU, leaving less leeway to member states.

Finally, responsibility-sharing is not confined to the provision of refugee protection anymore but is combined with the objective of migration management. The New Pact blurs the lines between refugee protection and immigration enforcement by streamlining procedures that were originally kept separate, like the handling of an asylum claim and a return procedure. In practice, this means that countries can contribute to European solidarity not only by pledging relocations within the EU but also by funding capacity-building measures to assist other member states. The new border procedures, that cover every aspect of the migrant journey from the screening at the arrival to an expedited return if there are no grounds to grant the right to enter the EU, are another clear example of this.

With these measures, the New Pact translates the solidarity principle into concrete policy measures in the main body of secondary law (legal acts that stem from the EU treaties’ provisions and principles). Thereby, the rules for responsibility-allocation (Dublin criteria) are complemented with an arrangement for active solidarity between member states, which has been largely absent from EU migration policy. However, the flexibility and discretion offered to member states to fulfill their solidarity obligations under these clauses indicate the compromises that had to be made to overcome the previous failed attempts to inject solidarity into Dublin. Yet, the establishment of a new solidarity mechanism and a solidarity fund represents a step forward in the institutionalization of solidarity among member states.

In sum, the New Pact is a compromise to accommodate the opposition towards the mandatory relocation of asylum-seekers while largely maintaining Dublin responsibility rules. This has been the price to pay for finding a common political ground among member states. The result is that the EU’s commitment to responsibility-sharing becomes broader, involving the sharing of norms, money, and people, and providing member states the flexibility in their contributions to enhanced solidarity, ranging from relocating refugees to enforcing migration management.

Will It Make a Difference?

While the European Commission is eager to demonstrate bold action and effective problem-solving ahead of an election cycle with anti-immigration forces poised to make big gains, the big question is: Will this deal lead to more solidarity and a more equitable sharing of protection responsibilities? Reaching a political agreement on the key texts of the New Pact is undoubtedly an important milestone for EU migration and asylum policy development. Substantively, the move to a flexible and multi-dimensional model of responsibility-sharing should allow for the accommodation of the different circumstances of member states and the differentiation of solidarity contributions can make the system more efficient. There are however two major challenges that will ultimately limit the impact of the reform on responsibility-sharing.

First, the new rules and instruments only work if they are implemented and stakeholders are willing to comply with them. The political agreement is one on the general principles, whereas the technical details are still contested among member states. Moreover, the provisions of the New Pact have been qualified as very complex, casting further doubts on an effective practical implementation. Together with the leeway and flexibility that the New Pact provides to member states, this means that significant political will is necessary for the new rules to work in favor of more solidarity.

Second, the structural imbalances in refugee arrivals and their institutionalization by the Dublin criteria to assign responsibility based on first entry will be largely left unaltered, notwithstanding the inclusion of an extended scope of grounds for family reunification or ties with an applicant’s educational attainments in an EU member state. As a result, the frontline states in the EU’s periphery will still receive most arrivals and consequently be responsible for processing their asylum request. The incentives for states to facilitate and for asylum-seekers to engage in secondary movements will therefore hardly wane.

Overall, the New Pact does not revolutionize European migration governance and is rather a pragmatic modification of the system of responsibility-sharing to overcome the political deadlock. We should therefore not expect wonders but at best incremental efficiency gains from a more flexible approach.

Maud Bachelet is a PhD researcher at the University of Geneva working on the politics of responsibility-sharing in the EU. She is an associated researcher to the NCCR project “The Impact of Crises on the Governance of Migration.“

Philipp Lutz is a senior researcher at the University of Geneva and an assistant professor at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He is an FNS Ambizione grantee for the project “Connecting countries and dividing people: The politics of burden-sharing in times of contested globalization.”