History That Fades Away? The Long Farewell of Anti-Fascism as Civil Religion in Italy

Italy’s complex history, marked by a century-long fragmentation, a difficult unification, a liberal period followed by 20 years of fascist rule, as well as persisting political and cultural divides, makes it challenging to define a cohesive national identity. Italians historically often felt a stronger connection to their municipalities than to the country as a whole, influenced by the enduring role of religion. Anti-fascism as a civil religion was able to create a lasting glue for a fragmented society over four decades. Recent political shifts have, however, reignited fears about the lingering influence of Italy’s fascist past, highlighting the country’s struggle to balance its centrifugal identities with a shared political commitment to liberal and anti-fascist values.

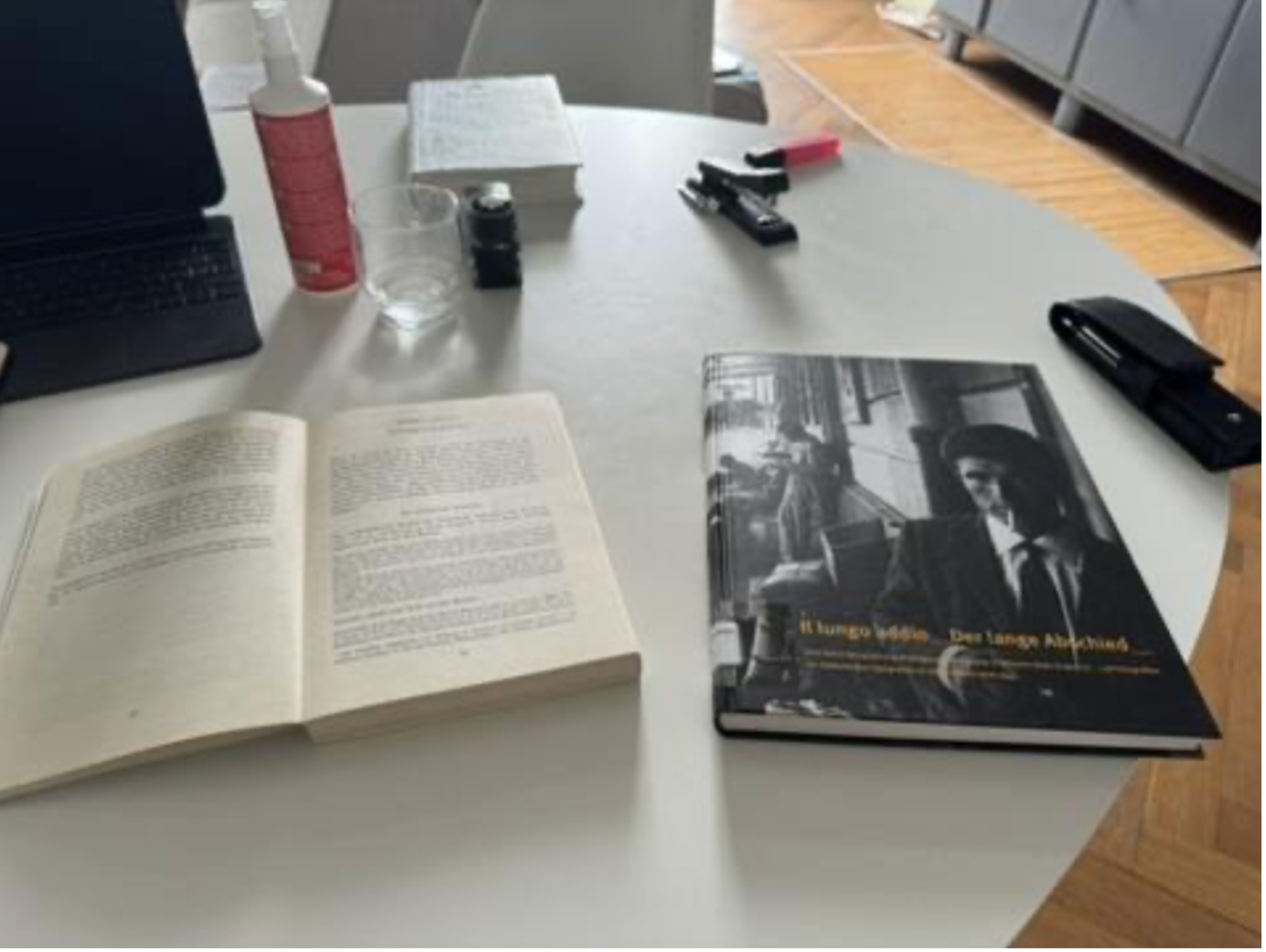

“Il lungo addio,” the final product in the form of a photographic history of the Dieter Bachmann era at the Istituto Svizzero (ISR) in Rome (2000-2003), was dedicated to all Italians who came to work and live in Switzerland. The photo book begins with a picture by Christian Schiefer showing the publicly displayed corpses of dictator Benito Mussolini, his lover Clara Petacci and a companion. They were seized by partisans a few days after the liberation while fleeing north, and executed by order of the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale Alta Italia (CLNAI), in which the later President of the Republic Sandro Pertini was also involved.

The end of the fascist dictatorship and liberation from German occupation could only be achieved with the support of the Allied Forces. The resistance struggle, in which a non-partisan committee of parties was involved, signaled a generational break with the regime as well as the dawn of a new era.

Twenty years of fascism, however, had not left people’s mentalities unaffected and many authoritarian attitudes were passed on. Nevertheless, the Republic was proclaimed (beautifully portrayed in the recent film “C’è ancora domani” by Paola Cortellesi) and a constitution was drawn up in the spirit of anti-fascism.

Eighty years later, and one hundred years after the murder of Giacomo Matteotti, a socialist MP opponent to fascism, Italy is governed by a radical right-wing coalition with Giorgia Meloni, as the tactically shrewd Prime Minister, who wants to secure political power for their parties through an announced electoral reform (for the historical parallel in the 1920s, see Gentile 2023).

This shift in governance leads me to question whether we might be observing a long farewell to anti-fascism as Italy’s civil religion. With this in mind, I decided to dedicate my stay at the ISR to examining this question, which requires some clarification before the actual research can begin.

Italy as an Imagined Nation

The idea that Italy is challenged by a low level of mutual trust is a constant theme in its contemporary reflection (see Robert Putnam’s book “Making Democracy Work”, Princeton 1993, his Italian and US critics in: Sabetti 1996, Tarrow 1996, Edwards 2010). The literature is legion denouncing a widespread lack of “moral resources” of a modern community of citizens, which would require a degree of shared commitment to overarching values to form a cultural community defined by those values, the definition of civil religion.

The notion of “many Italies” has been prevalent since the nation’s birth in 1861. Loyalty to family, local community, the church, and formerly political parties — though this has strongly diminished since 1989 — has traditionally been stronger than loyalty to the nation, shaping Italian social actions over the decades.

Despite their limited strength, the objective presence and effectiveness of national ideas in Italian political culture cannot be denied either. Italian political culture had different conditions for developing a civil religion understood as a “philosophy of the citizen” encompassing moral convictions, political options, social classifications, and perceptions. In the U.S., contrastingly, civil religion is a paradigmatic example of a democratically understood religious interpretation of national history.

In this line of thought, in the process of political self-assertion, the Christian citizen abstracts from himself or herself as a Christian and adapts to the civic roles within a liberal political system, which in turn relies on prerequisites and values that a liberal society itself cannot guarantee (Böckenförde 1976). The contradictory and influential role of Catholicism and the Church in Italian history — especially during the 19th-century unification process known as the Risorgimento — and within Italian society creates particularly challenging conditions for developing a civil religion.

Unlike the U.S., Italy does not have over two hundred years of uninterrupted republican-democratic tradition, although this US model shows also signs of erosion in the recent past. In the 163 years since national unity, Italy has experienced three different forms of government: a monarchy from 1861, a fascist dictatorship from 1922, and a democratic republic only since 1946.

A Civil Religion

The three historical moments important to the debate on civil religion were: the Renaissance, the Risorgimento, and the mentioned Resistenza (Campani 1993).

During the Renaissance, Nicolò Machiavelli held an important role, as an advisor to Lorenzo de’ Medici, ruler of the Florentine Republic, in unifying Italy through cooperation with Milan, Venice, and Naples, while challenging France’s ambitions in Italy.

Machiavelli’s writings offer an early example of Italian identity, rooted in the illustrious political myth of ancient Rome. His reflections highlight a critical issue for Italy’s nation-building: the presence of the Papal States. Machiavelli developed a republican tradition critical of the Church, viewing religion’s influence on social integration and political legitimization as a significant obstacle to the unification of Italy.

The Risorgimento (1815-1861) was the period in Italian history when political and social movements led to its unification. This period concluded in 1870 with the capture of Rome, marking the completion of Italian unification. In all conceptions of the Italian nation, the reference to ancient Rome plays a central role as a symbol of an immortal civilization and the core of national identity. Every high point in the national history is seen as a new manifestation of its glorious past.

Italian identity exemplifies the “invention of a nation” based on a common cultural canon shared by a narrow intellectual elite. However, the initial conditions were particularly unfavorable characterized by large economic disparities, considerable cultural fragmentation, and the absence of a large national bourgeoisie and strong social fragmentation.

The situation became even more harmful during fascism, which practiced a divisive totalitarian political religion, based on the glorification of war, violence, and submission. The organization of nationalist symbolism in an organic “national religion,” which had been lacking until then, was probably the real novelty of the fascist ideology.

Following two years of a war waged (1941-43), Italy was only able to avoid an early defeat in the Mediterranean with the help of its German ally. The landing of the Allied in Sicily in the spring of 1943 sealed Italy’s military defeat. It was during two years of resistance (1943-45) by the formerly illegal political organizations from the left to the center against the Republic of Salò and the German occupation, and this civil war, which was also a war of classes and liberation (Gian Enrico Rusconi, Se cessiamo di essere una nazione, Il Mulino 1993), that an anti-fascist civil religion was formed.

The cardinal points of this civil religion were Italy imagined as a constitutional democratic republic as well as the commemoration of those who shared the values of antifascism and gave their lives for the republican transformation of Italy, which is commemorated particularly on the Liberation Day of April 25.

The examination of these rites of commemorations in Parliamentary speeches, from the Cold War to the crises of our days, led me to the research I will carry out following my stay at the Istituto Svizzero and my sabbatical leave in Naples this fall.

This blog article was adapted from the original article published by the Instituto Svizzero to fit our nccr – on the move blog format.

Gianni D’Amato is a Professor at the University of Neuchâtel, the director of the nccr – on the move, and the Swiss Forum for Migration and Population Studies (SFM).

References:

–Bellah, Robert N. (1967): “Civil Religion in America.” Daedalus, 96 (1), 1-21

–Böckenförde, Ernst-Wolfgang (1976): Staat, Gesellschaft, Freiheit. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp 1976.

–Campani, Carlo (1993) Antifaschismus als Zivilreligion. Zur Rekonstruktion des Zivilreligionsbegriffs und seiner Anwendung am Beispiel der italienischen Republik. Frankfurt: non-published Ms.

–Edwards, Lindy (2010): “Re-thinking Putnam in Italy: The role of beliefs about democracy in shaping civic culture and institutional performance.” Comp Eur Polit 8, 161–178 (2010).

–Gentile, Emilio (2023): Totalitarismo 100: Ritorno alla storia, Salerno: Salerno Editrice.

–Müller, Alois, und Heinz Kleger: (1986) Religion des Bürgers : Zivilreligion in Amerika und Europa. München: Ch. Kaiser.

–Putnam, Robert (1993): Making Democracy Work, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

–Rusconi, Gian Enrico (1993: Se cessiamo di essere una nazione, Bologna: Il Mulino.

–Sabetti, Filippo (1996). “Path Dependency and Civic Culture: Some Lessons from Italy about Interpreting Social Experiments.” Politics & Society 24 (1): 19–44.

–Tarrow, Sidney (1996): “Making Social Science Work across Space and Time: A Critical Reflection on Robert Putnam’s Making Democracy Work.” American Political Science Review 90 (2): 389–397.