Blind Spots and Uncertainties – Juggling Knowledge During the Pandemic

There are two kinds of uncertainties we as researchers are faced with: There are those things we are aware of that we do not know, but also those we are unaware of that we do not know. Dealing with this range of uncertainties can be demanding in ‘normal’ times and even more so during such unusual times as we are experiencing currently. While these are uncertainties any researcher must face, some uncertainties are particularly challenging for early-career researchers.

Although not starting completely from scratch, early-career researchers still have a lot of things to learn or improve: reading efficiently and critically, conducting research, creating knowledge, working within and around hierarchies, communicating and presenting research, receiving and giving feedback, networking and building a career. These diverse tasks lead to the acquisition of a variety of skills – yet there is one thing they all have in common: working with uncertainties.

Known Unknowns and Unknown Unknowns

Two important questions for any researcher are: What else is there to know, and how can we learn more about it (Grix 2002)? The first question relates to things that we do not know of yet – and the second relates to the actual process of researching, examining, studying, and explaining. As illustrated in the following table, and popularized in a controversially received speech of former United States Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld in 2002, the awareness of our own knowledge can be divided into four fields: First, things we are aware of that we know (we are aware this text is written in English). Further, things we are aware of that we do not know (like when exactly the COVID-19 pandemic will be over, if ever). Then, there are things we are not aware of that we know (of which it is hard to make an example of, because the moment we become aware of something we are normally not aware of, it shifts to the first box). Finally, there are things we are unaware of that we do not know, which are absolute blind spots.

| Knowns | Unknowns | |

| Known | Being aware of what I know | Being aware of what I don’t know |

| Unknown | Not being aware of what I know | Not being aware of what I don’t know |

This categorization might seem like a fancy way of organizing knowledge, in a way that knowledge travels from one box to the other, i.e., from being an unknown unknown to being a known unknown and then, if everything goes well, to a known known (Maasen 2015). However, if we think of knowledge as being infinite and not existing on a limited continuum between what is known to us and what is not, then the more we learn about something, the more we also realize how much we do not know about it. Thus, in creating knowledge, we also always create more unknowns – and we can be assured there are more blind spots for us to discover or to remain unnoticed.

The Impact of COVID-19

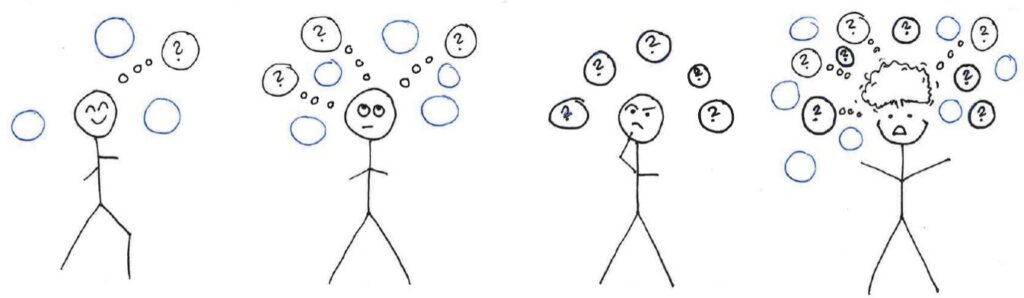

Figure 1: A junior researcher dealing with (un)known unknowns and the impact of COVID-19, i.e., the rise of uncertainties. Unknown unknowns (i.e., blindspots) are presented as blue circles, known unknowns as thinking of a black question mark, and unknown unknowns that have already been wondered about as a black question mark in a circle.

While early-career researchers must get used to dealing with blind spots and known unknowns around them, the guidance of experienced researchers is central in learning how to work with such uncertainties efficiently and effectively. Under ‘normal’ circumstances, especially when drawing upon the experience and guidance of senior researchers, the amount of (un)known unknowns seems manageable (picture 1).

However, COVID-19 and the emergence of various restrictions all over the globe present an unclear increase of known unknowns (picture 2). Suddenly, it is uncertain whether fieldwork can be conducted as planned or a fellowship completed (and even if it can, whether a fellowship stuck in home office, communicating online with the team you were supposed to work with locally makes any sense at all). Mobility restrictions and border closures are not just a thing to be studied (for migration and mobility researchers), but they become a salient challenge to face in one’s daily life.

However, while these uncertainties (of which we are aware) grow – the question arises whether our blind spots increase as well (picture 3). While unknown unknowns do not yet transform into known unknowns, we can still contemplate about what else might be out there that we do not know about. The sum of these unknowns (both known and unknown) can lead to a situation that might paralyze and/or alarm us (picture 4). While this is a reality for everyone, it poses a particular challenge for early-career researchers: Not only might early-career researchers struggle to deal with the uncertainties the pandemic is causing both in relation to our private lives and in regard to conducting research, but the well-known academic structures and rituals (conferences, etc.) are no longer functional – for anyone of us. That also means those who usually function as guides are ‘out of order’, as nobody, including professors, has experience on how to conduct research during a global pandemic and how it might affect the future of academic structures and life. Further, we come into this novel situation from very different starting points and the inequalities caused by, e.g., job (in)security are only amplified, potentially leading many early career researchers to rethink their future in academia.

Back to The Known Knowns?

With all its challenges the COVID-19 pandemic also presents an opportunity to pause and re-assess. While the instinct to fall back on old structures and mechanisms that we know to (sort of) work (for some) is completely understandable, this may be the moment to be brave and venture toward the unknown. Both by re-inventing academic structures collectively as members of the academic community and on the individual level of the researcher by reflecting on our role within these structures: Is the current hierarchical pyramid of academia really the best way to increase our collective knowledge? How much mobility or flexibility of researchers is necessary? How can equal participation from researchers around the globe be ensured? Is the counting of high-impact journal publications really a fair measure, when we are realizing how unlevel the playing field can be?

Change can be scary, but if this pandemic has shown us one thing it is that humans are encouragingly creative in their quest for solutions and adapt even to the most uncertain situations. While we do not have clear answers to our questions and the ones we did not even think of, we extend the invitation to you, fellow researchers of all seniority, to actively assist junior researchers in finding ways to tackle the situation illustrated in picture 4. Let’s put our heads together, let’s think about alternatives, and let’s venture toward the unknown unknowns…

Petra Sidler and Mia Gandenberger are doctoral candidates at the University of Neuchâtel and at the University of Lausanne. Both are fellows of the nccr – on the move: Mia is part of the project Welfare: Inclusion and Solidarity and Petra contributes to the project Overcoming Inequalities in the Labor Market: Can Educational Measures Strengthen the Agency and Resilience of Migrants, Refugees, and their Descendants.

References:

– Grix, J. (2002). Introducing students to the generic terminology of social research. Politics 22(3), 175-186.

– Maasen, S. (2015). Wissenssoziologie. Transcript Verlag.