Non-Citizen Voting Rights: A New European Network

As borders closed and countries shifted to a national focus, establishing lockdowns and social distancing measures, these extraordinary circumstances actually sped up the creation of a new network linking six initiatives in different European countries striving to obtain voting rights for residents without the local citizenship.

Current debates and protests against racism highlight once again the need to address racism, exclusion, and discrimination at institutional levels. This also includes equal political representation and presence of all residents.

Why is Political Representation an Issue?

Insufficient representation is not just an issue of a lack of politicians with migration histories or a lack of passive voting rights and consulting organizations, but also a lack of active voting rights. While many countries provide local voting rights for non-citizens (e.g., 17 countries in Europe with different forms and conditions), many others do not. High percentages of local populations, who do not have the citizenship of the countries they reside in, have thus limited influence in politics. To illustrate, around 25% of residents in Switzerland and 12% in Germany including EU citizens, 7% excluding EU citizens, are residents without local citizenship.

Naturalization is not always a solution. Especially in Switzerland, it can take 10-12 years of continuous residence to be allowed to apply, which can contradict the mobile biographies of contemporary migrants. Additionally, it is costly (e.g., up to ca. 2000 CHF in Basel-Stadt) and, at times, impeded by other obstacles in the countries of citizenship. There has thus been an ongoing debate about citizenship, participation, and voting rights during the last years.

Struggles for More Inclusive Voting Rights

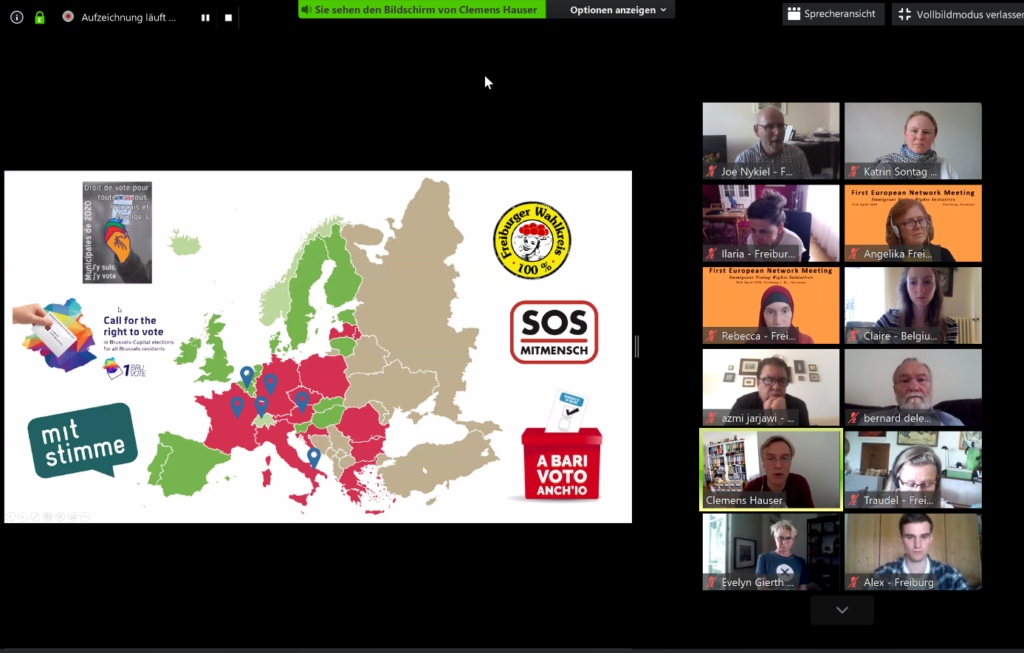

In several European countries, initiatives have been campaigning for introducing voting rights for residents who do not have local citizenship (e.g., after 5 years of residence). Six of these initiatives from different European countries have now initiated a new network at the end of April 2020, and our research team participated in its organization and meetings.

The six initiatives use different strategies for promoting migrant political participation and voting rights. Some of them carry out symbolic elections (in Freiburg, Bari, Paris, Amiens, and Austria). The elections run parallel to the official elections and allow those who cannot vote to cast their vote as well – based on the same list of candidates as in the official elections. The results are usually not very far from the official results (similar in Bari, more left-leaning in Austria, more CDU focused in Germany). Similarly, in the previous century, the campaigns for women’s voting rights in Switzerland involved symbolic voting, which serves as an example of the struggle towards better democratic representation.

Some initiatives also run polls for local citizens on whether they would favor migrant voting rights (e.g., Freiburg, Paris). The initiative in Brussels worked mainly with petitions in the local communes in Brussels and the Regional Parliament. They also collected signatures and filmed statements of politicians to make their cause more visible.

In Basel, the initiative “mitstimme” organized a symbolic parliament preparing topics and debates beforehand. The parliament sessions took place in 2018 and 2019 in the town hall of Basel. The debate’s results were handed over to local politicians for further discussion with the aim of being included in the political agenda. They also offered training on the political system and organized interactions with politicians, e.g., through speed dating sessions. Very recently, the parliament of Basel decided in favor of non-citizen voting rights, a change of law that now has to be approved by a referendum within the next two years. For this process, Basel’s initiative, “mitstimme,” has started a new campaign.

Connections in Times of Corona

Despite closed borders, initiatives have formed a network to collaborate and share their experiences internationally online. In fact, the extraordinary circumstances of the lockdown provided more flexible schedules and the necessity to use technology that, in turn, saved travel time and money.

The network meetings not only showed similar issues, struggles, and arguments in different countries, even if the contexts were different, but also that activists used similar strategies. Still, even though joint campaigns are possible, the legal changes the initiatives work towards are decided on cantonal or national government levels. It is yet an open question in most countries, how the topic will develop, and how social cohesion and awareness might change if more migrants were voters and not seen as “non-citizens” without a political say.

Katrin Sontag is a cultural anthropologist at the University of Basel and PostDoc in the project Perimeters of Multilayered Democratic Citizenship in a Mobile and Multicultural World.

Related article: